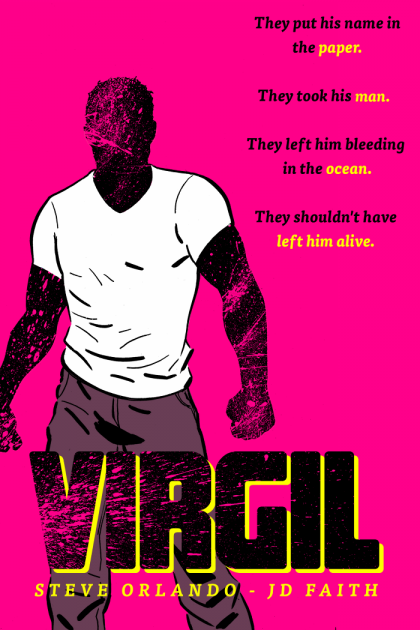

Intersectional narratives about marginalized groups tend to be relegated to a certain genre. If a story is going to deal with complex issues of race, gender or sexual orientation, there’s this frustrating sense that they can only exist as stark, self serious dramas. Virgil, the original graphic novel from Midnighter writer Steve Orlando and artist JD Faith, smashes those preconceptions with this thorny, taboo-tackling revenge thriller. The titular Virgil is a crooked police officer operating in Jamaica. He spends his days with partner Omar shaking down drug dealers and buying other cops drinks with the spoils. At the end of a shift, he’s just as likely to hit up a whorehouse with his best mate to celebrate. But this is all a front.

Virgil’s entire life is an elaborate cosplay of stereotypical masculinity. It has to be to keep himself and his lover Ervan safe. Despite being a huge tourist attraction, Jamaica is a hotbed of violent homophobia. This tragic dichotomy is brilliantly illustrated in the book’s title credits, where a white woman hooking up with a local at a hotel is juxtaposed with someone being jumped and assaulted. Virgil has been saving up his ill-gotten gains to get him and Ervan away from this place to Toronto, where they both dream of walking down the street arm in arm and eating in public restaurants together. It’s terrifying that such modest aspirations seem so towering while trapped inside of this waking nightmare.

Things take a turn when Virgil and Ervan are attacked with a group of their queer friends. The attackers capture Ervan with the rest of the dinner party, slaughter most of the attendees and leave Virgil for dead. When Virgil awakens, he discovers that he’s been outed in the press, putting a giant target on his head from gangsters like Bandulu, one of the vice peddlers he’s pilfered from. The book takes a sharp turn into exploitation territory as Virgil sets out on a non-stop spree of gorgeously choreographed violence to get his boyfriend back and get vengeance for his fallen friends.

On a purely visceral level, the action-centric middle third of Virgil is a work of art. Divorced from any narrative context, Faith draws these shootouts and fist fights with a crackling kinetic energy that splits the difference between the flat pencils of a David Mazzuchelli with the off-kilter layouts and dynamism of Jack Kirby. This dichotomy between realism and the extra real vibrance of genre gives Virgil a unique flavor best exemplified in Chris Beckett’s expressive color work. Bathing scenes in stark lighting tinged with a bright, neon hued palette implies the chiaroscuro of film noir cranked up to absurd levels of incandescence. In the midst of this righteous fury, Virgil feels like a grindhouse movie, but it’s executed with a voracity only comics can contain.

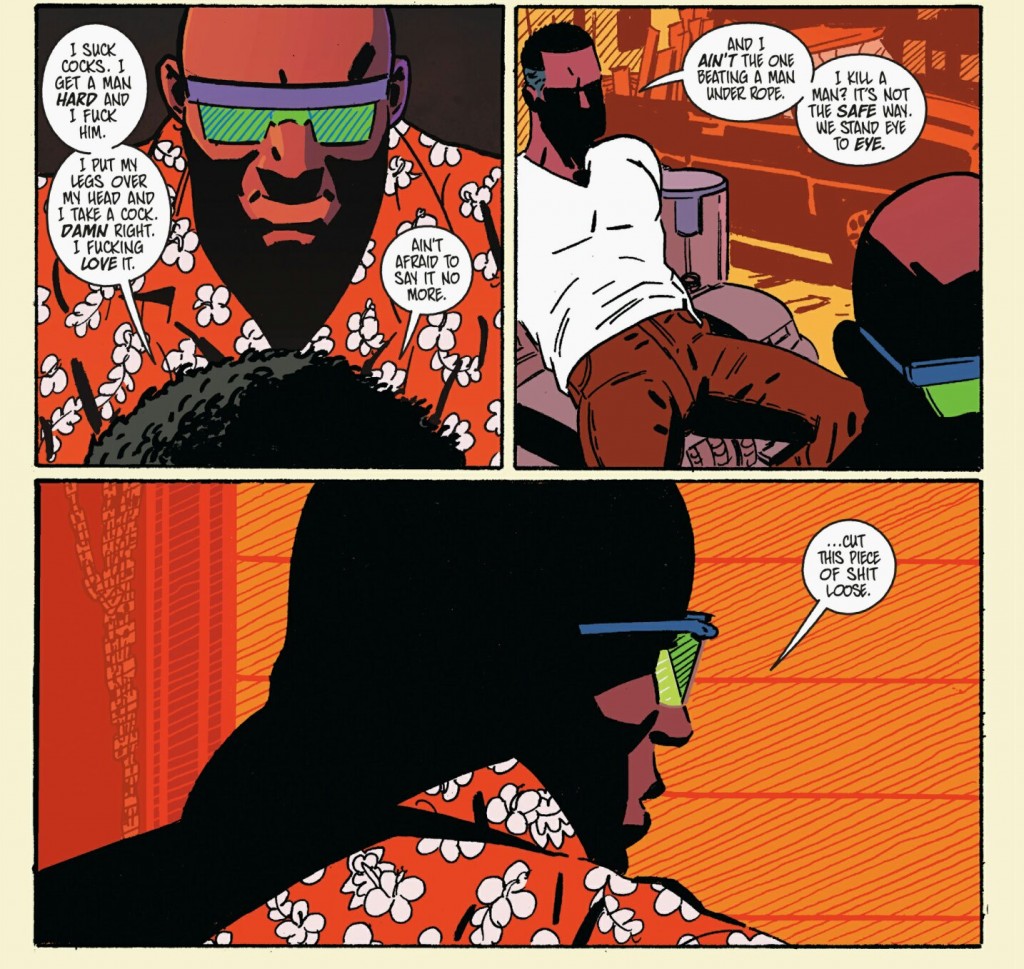

If it was just a John Wick style actioner, Virgil would be a success based on nothing but aesthetics, but Orlando and Faith use this pulpy framework to comment on the duality of masculinity with efficacy. Both sex and violence are depicted with a two-handed approach. When we see Virgil feigning interest in brothel-based coitus, we’re made to feel repulsed at the masquerade act, framed at a close enough distance to see the barely hidden disgust on his face. But when we see him and Ervan in bed for the first time, the “camera” comes in much closer, painting a warm intimacy over the act that feels comforting, like home.

Similarly, the action transmutes the ugliness of the violence with a subtle hint of gay male gaze, highlighting the masculine form from tawdry angles, forcing even the homophobic antagonists of the narrative into a homoerotic light. It’s queersploitation at its finest, as our hero Virgil emerges from having his manhood questioned and attacked looking even more potent and confident, empowered by the will to find his man.

The climax of this awakening occurs in a tense standoff with Bandulu. We’ve seen Virgil’s hard man act and we know he’s a capable fighter, but so much of his brute force is a put on. He’s violent and tough because that’s what other men expect him to be. There’s a weakness to his strength, because it’s rooted in self denial. But once this fire is lit beneath him and he’s driven to save the man he loves, a more viable strength comes to the fore. His homosexuality and his masculinity cease to be mutually exclusive terms. His love for and attraction to another man shows him to be more of a man than these interlopers, not less of one.

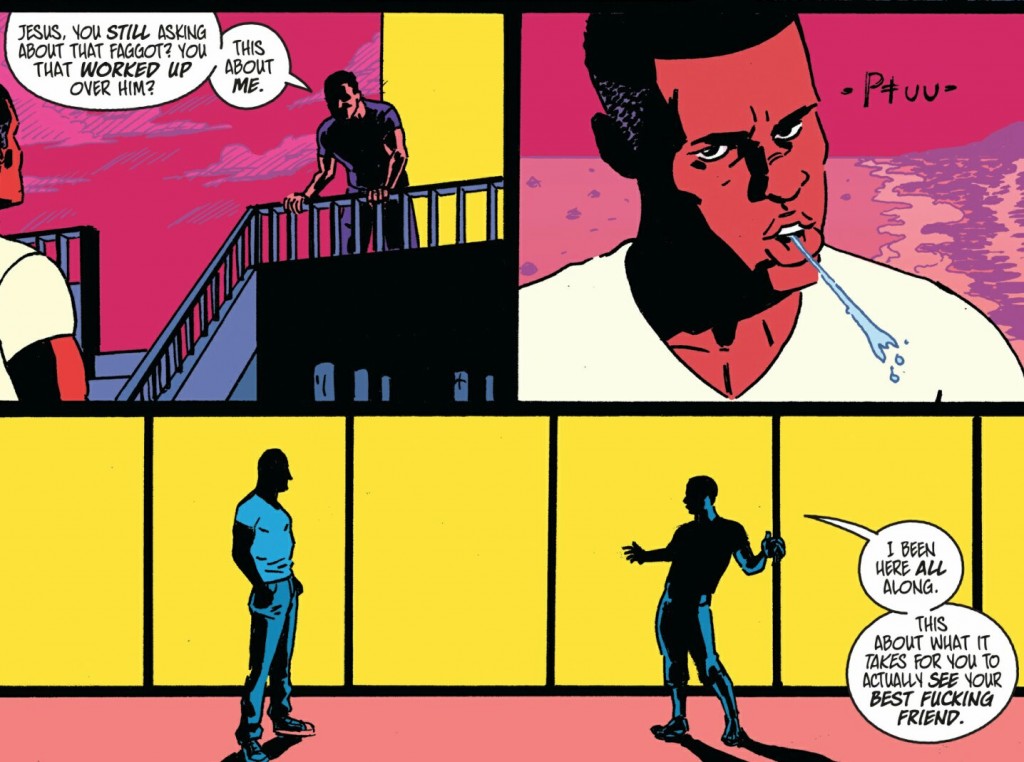

The book also deftly torpedoes the strand of gay panic on display in so many stories about bromance. Virgil comes to find in the closing act that his partner Omar is behind the whole thing and he’s got Ervan strapped seductively to a chair in the beach house Virgil never finds time to visit. The bitter jealousy Omar displays would be tragic if he wasn’t so demonstrably a piece of shit. Their final showdown draws a definitive line in the sand between Virgil’s two primary relationships: the make-believe brotherhood shared with Omar, rooted in the recreational abuse of criminals and a toxic brand of decadence versus the everlasting bond forged with Ervan, the one that allows Virgil to be his truest, best self.

Virgil is a testament that stories of diversity, representation and acceptance don’t have to be bound to vanilla weepies about intolerance. That same cathartic exploration can occur even in a gritty shoot-em-up. It’s all in the execution.