Have you read this bullshit? It doesn’t seem like a lot of people on Film Twitter have, and yet, somehow, the collective jerk-off motion they made last Saturday over Ty Burr’s opening sentence in his Boston Globe op-ed—”Someday we may look back on 2016 as the year the movies died.”—may actually be an underreaction.

Oh, sure, he makes some cogent points about how the big pop culture touchstones of this year, so far, have been long form TV narratives like Stranger Things or conceptual music video pieces like Beyoncé’s Lemonade, and throws around some box office numbers worth paying attention to. Yet, it’s still in service to an embarrassingly facile conclusion that sinks far beneath the standard of a publication as celebrated as The Boston Globe, one that says more about what film journalism has become than what two-hour movies have become. Seriously, it’s supposed to be a page out of our playbook: start with a splashy, attention-grabbing statement, and cherry-pick evidence to support it. That doesn’t mean you don’t believe it—although in this case, Burr certainly hedges in the very next sentence by admitting he’s making a blanket statement—but you’re mostly rolling with it because you know it’ll pick up lots of clicks and social media buzz, thus elevating your profile. Good or ill, you still get eyeballs and you still get paid. If that’s what the entertainment editors of The Globe want, they should just bite the bullet and hire Devin Faraci already.

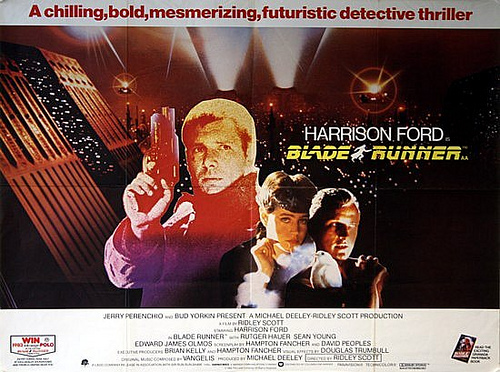

Whatever; I’m clearly taking the bait, so I’m not going to pretend to be above the fray. Instead, let’s just use this opportunity to talk about how movies, as an idea, are bigger than the zeitgeist. Because that’s the real problem of the piece: he conflates the importance of movies with their pervasiveness in pop culture and the financial and critical success they do or do not achieve. I mean, right off the bat, Blade Runner should caution anyone against using current critical reactions as a measurement of how movies, as an artform, are currently doing. Take a look at Roger Ebert’s three-star review of the film. Note the following:

The movie’s weakness, however, is that it allows the special effects technology to overwhelm its story. Ford is tough and low-key in the central role, and Rutger Hauer and Sean Young are effective as two of the replicants, but the movie isn’t really interested in these people — or creatures.

Roger Ebert, one of the most celebrated populist film critics of our era, missed the point of the movie when it first came out. It went over the equally celebrated and far more intellectual Pauline Kael’s head, too:

A visionary sci-fi movie that has its own look can’t be ignored: it has its place in film history. But you’re always aware of the sets as sets-it’s 2019 back lot. And the movie forces passivity on you. It puts you in this lopsided maze of a city, with its post-human feeling, and keeps you persuaded that something bad is about to happen…but [Harrison] Ford’s mission seems of no particular consequence. The whole movie gives you the feeling of not getting anywhere-of being part of the atmosphere of decay.

None of this is to say that you absolutely must agree that Blade Runner is a great movie. You cannot, however, deny the reach it ended up having, and if you crunch the numbers, you’ll know that Blade Runner didn’t make its way into The Pantheon on the sole strength of how most people felt about its set design and special effects. Yet, Kael and Ebert’s initial impressions (Ebert eventually turned around on the movie) would suggest those evolutions were all that Blade Runner brought to the table.

To say, then, that movies are dead because you don’t see any quality or cultural relevance in this summer’s multiplex offerings is to suggest that you are a more prescient film critic than Roger Ebert and Pauline Kael, two of the most respected and thoughtful writers to ever come out of the field. The zeitgeist is the zeitgeist. People revisit, reevaluate. Opinions change. You can talk all day about Stranger Things being the cultural event of the summer, but I’m already seeing backlash to the show that goes beyond Vice telling The Internet to shut the fuck up about Barb already.

Meanwhile, for all the critical failures of the theatrical cut of Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, I’ve had no less than three heavy conversations about the themes of the movie with friends, and I know I’m not alone. Moreover, if you believe our own David Uzumeri, then the so-called “Ultimate Cut” of the film solves most, if not all, of the theatrical cut’s problems. I honestly don’t know if a movie in this day and age can be a sleeper phenom the way Blade Runner was, as opposed to a mere cult classic. If any film has a shot at it, though, it’s Batman v. Superman, and if perceptions on the film do turn around, a statement like “movies died in 2016” is going to look even dumber should it ever be unearthed.

Even if they don’t, so what? Blade Runner is merely an example of how the zeitgeist that determines cultural cachet can ignore something truly wonderful, only to warm up to it over a period of years. Maybe that doesn’t happen; maybe excellent, underseen movies like Sing Street, Pete’s Dragon, or Kubo and the Two Strings are destined to remain hidden gems. Does that mean we’re going to see less of them? I don’t know, but people have been crying about that same damn wolf since the one-two punch of Jaws and Star Wars. But the movies keep getting made, and the only fundamental shift I’ve seen is in how platforms like Netflix might allow even more of them to be made (even if that means cutting out the luxury of a theatrical run).

I remember walking on air after getting out of Brooklyn last winter, thinking “They don’t make them like that anymore,” then realizing that I might have said that about three other films in that year alone: Burnt, Spotlight, and Ricki and the Flash. Spotlight took home Best Picture, however unexpectedly. And before someone calls bullshit on the implication that Burnt or Ricki are good films, A) I’d be happy to defend them, and B) Burr had the balls to claim that Free State of Jones was an example of a film that didn’t make any money because of this suffocating climate. Not because it was distributed by a new/new-ish company still getting the hang of how to schedule and promote their product to ensure maximum viability at the box office. Certainly not because it was promoted as a Civil War-era action epic, only to end up being a nearly 2 1/2 hour exercise in misery that took a fascinating story on paper and made it seem somehow pointless in practice.

I’m sure Burr sees the film differently. If we ever talked about it, we’d probably end up agreeing to disagree. That’s fine, because the reason movies will persevere in the face of any wave of mass commercialization is because, like any artform, the appreciation of movies is as personal as it is universal. It’s been the struggle of the critic ever since criticism became part of the conversation: how to reconcile objective standards with subjective tastes. The omnipresence of a thing in pop culture, however powerful it may seem, is a mere aggregation of how the public feels about that thing. It’s certainly not nothing, but at the end of the day, the personal view will always win out, because it will always be a viewer’s compulsion to judge quality and relevance for themselves. That’s how Blade Runner went from an example of empty Hollywood spectacle to one of the most important sci-fi films of the late 20th century, and it will be the ultimate reason why small, great movies will continue to get made.

I know I dragged my father to Midnight Special—refusing to tell him a single word about it beyond “father/son road trip”—because even though he tends to prefer mainstream studio films, I knew it would blow his goddamn mind. Boy, did it ever. I know I’m going to force every friend I make to watch The Nice Guys at some point. I might even judge them a little if they don’t think it’s a perfect movie. I know that Triple 9 came out just when my college buddy and I were looking for something a little more hard-edged than the usual superhero fare we go out to see, and John Hillcoat didn’t disappoint us at all. And I know that when my niece and nephew start feeling the growing pains of their teenage years, you bet your ass I’m gonna be showing them Sing Street. They might trip over the heavy Irish accents at first, but by the time the movie launches into “Drive It Like You Stole It,” they’re going to be jumping on the goddamn couch because they’re going to feel like somebody gets it. None of these films really broke into the mainstream consciousness the way Stranger Things did, which is how Burr is trying to support his point. It’s natural to lament these small-scale tragedies, but if you allow that lamentation to cynically define the failure of an artform, I’m not really sure you get the point of art.

Look, it’s a minor miracle when any movie reaches my eyes; there’s a lot of movies on my list that I haven’t gotten to, including Everybody Wants Some!! and the recently released Hell or High Water. But they reach my eyes all the same. These movies don’t disappear because they fail to gross tens of millions and make twenty times as much overseas. They persevere because they inspire an individual passion that a movie like X-Men Apocalypse couldn’t, passion that motivates people like me to go to their friends and tell them to SEE THIS FUCKING MOVIE NOW, and the producers of these films—the Megan Ellisons, the Adi Shankars, the Duplasses, countless others whom I can’t name—are smart enough to know how to play to that so they can stay in business. True as it is that only a lucky few films seem to break out anywhere near the mainstream each year, they still break out, and they remind us that movies are more than surface-level exercises in visual and visceral acrobatics.

“The year movies died.” There’s no good witticism here, no clever twist of words that feels like an appropriate response to such a statement. There’s only a palm to the face and a shake of the head.