I’m Chuck Winters, I’m on the spectrum, and the concept of this movie—an emotionally charged thriller with an autistic lead character from the director of Warrior—was pulled directly from fantasies I didn’t even know I had. Nice to meet you.

Let’s get a couple of things out of the way. First off, just because I have autism doesn’t make me an expert on the subject. There are people I know (and others I know of) who have done enough legwork to literally put me to shame, and have better informed themselves about their disorder. At the risk of putting them on the spot, some may feel differently about this movie than I do, which leads me to my other caveat: I can’t speak for everyone. Sure, that applies to pretty much any single person belonging to a specific social construct like race, gender, or common disorder, but in this case it rings especially true. There’s a reason autism is seen as a spectrum disorder, and that’s because it manifests in different ways and intensities from person to person. Some have the classic symptoms: not liking to be touched, reacting poorly to sudden loud noises, having trouble with eye contact. Others, like myself, are better about these things, but still have some minor troubles with social interaction and even some weird dietary issues. In other words, “If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.” Given that, it’s not fair for me to judge this movie strictly against my personal experiences. I can only judge it against how I see other portrayals of autism in film, and how that established baseline compares to my experiences.

If you can’t understand the difference between the two…well, welcome to my hell.

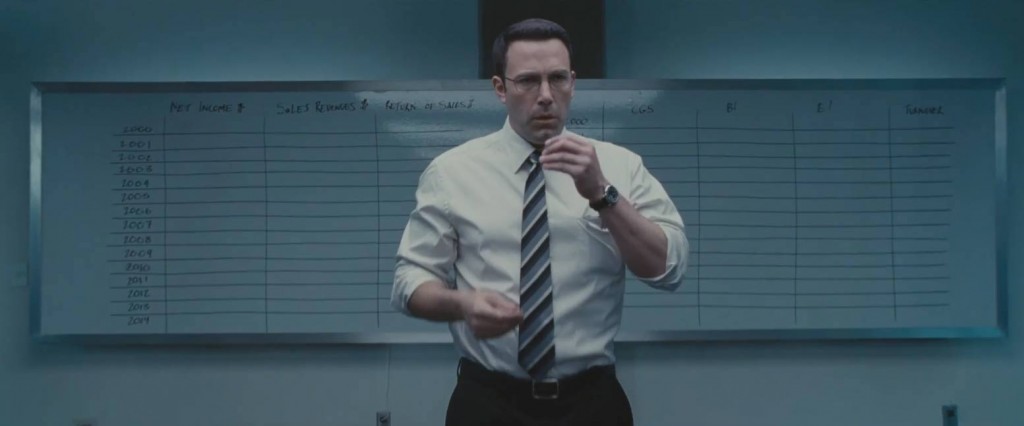

I’d like to jump right into Ben Affleck’s performance, but first, let’s make sure everyone’s up to speed on what this movie is. Affleck plays Christian Wolff, a CPA operating out of a busted strip mall in rural Illinois. Naturally, he’s far more brilliant and dangerous than his low-level stature would suggest: brilliant enough that he’s the guy you call when your ethically complicated business is missing money that needs to be found through forensic accounting, and dangerous enough that any smart person running an ethically complicated business knows not to fuck him over. You don’t untangle books from mobs and cartels without knowing how to bring down the fires of Hell the moment some nervous dumbass contemplates the word “liability.” While a U.S. Treasury analyst (Cynthia Addai-Robinson, last seen as the proto-Amanda Waller in Arrow) starts looking into him at the behest of her boss (J.K. Simmons), Wolff takes on a legitimate client: a robotics company where junior accountant Dana (Anna Kendrick) has found a strange discrepancy in the company books. Of course, Wolff turns that small tear into a very problematic hole, a charismatic hitman (Jon Bernthal) is called in to clean house, and Wolff pops the fuck off.

Right off the bat: Christian Wolff, as a character, bears a strong superficial resemblance to a far-too-traditional take on high-functioning autistics. He’s based mostly around logic, takes words far too literally, maintains an obsessively neat environment, is preternaturally talented in one or two specific areas, and doesn’t seem to do empathy. That last one tends to bother us a lot: It’s not that it doesn’t ring true, but one of the shittiest things about the “autistic” label is the risk that you’ll be written off by people as being unable to relate to them. In reality, more of us run against that stereotype than you might think. Plenty of us are warm, friendly individuals, and it kind of hurts that we keep getting written off in pop culture as being cold and unable to connect.

The Accountant seems deeply aware of that stereotype, though, even as it plays to it. In fact, playing to that stereotype might be part of the point. One of the film’s first scenes involves a specialist talking to the parents of a young Christian Wolff, bringing the audience up to speed on what autism is (it’s a view that would be super progressive for 1989, but Christian’s father is quick to balance that out with more typical hard-ass ignorance). In a different room, Christian is putting together a puzzle, being watched by a girl who appears to be far more non-functional: rocking in her seat, twitching, moaning. Just as Christian is about to complete the puzzle, he realizes a piece is missing. It is absolutely true that we can flip our shit when things don’t “work” the way they should (in Christian’s case, he needs to finish anything he starts), and Christian, having a grand total of one coping mechanism in place (he recites the nursery rhyme “Solomon Grundy”), proceeds to have a violent and thoroughly predictable meltdown.

That meltdown comes to a sudden end when the seemingly low-functioning girl presents him with the missing puzzle piece.

That’s the mission statement, right there: what society sees as broken may have it more together than they think, and not in the cloying, faux-philosophical “wow the retards have more humanity than us normals, makes u think” way. Christian grows into self-sufficiency thanks to his father’s efforts, but we learn that the same father also saw him as damaged goods—in his words, “different,” one of those turns of phrase that isn’t really wrong, but is deployed in an almost cruel-to-be-kind way. At one point, he openly admits to Dana that he wishes he better understood how to connect with people, but before that moment, you never see him making any attempts because, between the work he does and the lessons from his father, he always assumes he’s going to lose.

There’s a constant, understated war within Christian over whether or not he deserves normalcy. It’s a war some of us fight every day because we have internalized, as Christian has, this idea that we simply don’t belong. Hell, our biggest advocacy group keeps inadvertently putting this message forward in its quixotic and borderline offensive search for a “cure.” What The Accountant argues, through the exaggeration of genre filmmaking, is that Christian does have the emotional tools to live something of a normal life, criminal proclivities aside. Just like the girl he met at the autism retreat back in ’89, Christian may have trouble presenting himself as empathetic, but when the chips fall and the people he cares about are in trouble, there is no hand-wringing or second guessing: he has their back, full stop.

So yes, Christian is presented as a bit of a stereotype, but if stereotypes are reflections of how greater society views people of a certain “affliction,” then the film is presenting that stereotype in order to defuse it. Here, Christian isn’t blocked so much by his autism as he is by several extenuating circumstances, most stemming back to his father’s need to raise Christian in his own image, for good and for ill. The bigger question becomes, can Christian get over that lifetime of negative feedback from society at large and attempt to take that slice of normalcy that he’s interested in?

As far as I’m concerned, in conception, we’re already miles away from Rain Man or Mercury Rising here. In execution, Ben Affleck just crushes it as Christian Wolff. He resists the urge to go for a vocal affect (many of us, myself included, do tend to have a certain atonal lilt in our voices) and concentrates on physicality and mannerisms to his exceeding benefit. I personally think his key non-verbal tic (blowing on his fingers) was a little overblown, but it would take me five damn hours to explain why I feel that way, and in the end, it’s really not enough to damage the credibility of his performance. What he gets right matters far more. In one scene, he perfectly captures the way we tend to get really excited when we find something super-interesting within our hyper-narrow focus; in another, he nails the way we melt down whenever certain expectations we hold are completely upended—trying to control his panic at first, only to become gradually unhinged to the point where his usual coping mechanisms fail him. More impressively, though, he has this distant, wandering look in his eyes whenever he’s idle that gives me the impression that Christian Wolff really does view life through a unique and eerily familiar lens.

It’s one of Affleck’s best performances, and the rest of the cast steps up in kind. It’s not that they’re doing anything special, they’re just doing what they normally do to unusually great effect. Anna Kendrick pretty much Anna Kendricks across this typical love interest role, bringing her warm, dorky charm and a refreshing agency to Dana. She has surprisingly great chemistry with Affleck, and the ways she clumsily empathizes and connects with him are exciting and kind of adorable, giving the film a big emotional charge that carries its second half.

Elsewhere, Jon Bernthal, with his broken nose and righteous swagger, is having the time of his life as the film’s de facto antagonist; he’s introduced in a scene that would qualify him for his own damn movie, and his character remains fascinating throughout as a result. And J.K. Simmons is J.K. Goddamn Simmons, that’s almost all that needs to be said. There’s a dangerous moment where the movie stops cold—just as the third act kicks off, in fact—and walks you through what exactly has been going on. There’s simply too much information being dropped on you at once to fully succeed, yet it mostly gets away with it because of Simmons monologuing the hell out of it.

That’s really one of the few shortcomings of the movie; the story is a little on the convoluted side and isn’t all that efficient in parceling out what you need to know. I guess you can also say there are one or two twists you might see coming from a mile away, but if the value of a twist is how well they work knowing that they’re coming, then those twists remain priceless even as you put the final pieces together. Everything else about the movie is aces. Bill Dubuque’s script occasionally echoes Drive and calls for an eclectic blend of tones that could trip up a lesser director. However, Gavin O’Connor effectively zeroes in on the emotional spine of the story, expertly weaving it through the tense intrigue that primarily drives this film. As seen with Warrior, O’Connor is a dangerous filmmaker when he gets an opportunity to do this, and though he’s not as effective here, he knows how to use emotional stakes—combined with solid fight choreography, phenomenal sound editing, and some strong (if not necessarily juicy) squib work—to give his few action scenes a tremendous sense of immediacy and impact. Between all that, The Accountant establishes its own identity just fine.

If The Accountant told the same story with a neurotypical lead character, I suspect it still would have been a more-than-worthwhile genre exercise. With the autistic main character, it could have easily been gimmicky and obnoxious. But to me, there’s a clear sense that everyone involved did the work and strove to tell a story that respected our struggles and our humanity; it shows in the final result, a refreshing and rousing thriller that deserves to find its way into any given Saturday night “I Need To Watch Something Awesome” movie rotation. I know it’s going right into mine.

The Accountant is now in theaters.

My son being on the spectrum, I could imagine him writing this review. So many things, although small were done so right. Yes, Hollywood loves to exaggerate, but homework was done. Ben’s best preformance.