I first discovered Maxïmo Park in the middle of summer 2005. I was eighteen, and the assistant manager of a Hollywood Video, just entering the phase of life where I was obsessed with listening to “good music.” This meant loyally reading Paste, Blender, Under The Radar, and other magazines, curating a false taste in trends I hadn’t actually developed and snarking on any sounds that didn’t come packaged with a cache of cool. It wasn’t enough to be enjoyable. My music had to enrich my persona as an interesting, discerning person. CDs ordered from InSound felt less like physical media and more like individual plates for a suit of armor I was building piecemeal. Life was becoming something I needed proper protection from and I had zero qualms erecting a facade of mannered confidence and charming elitism between myself and the world.

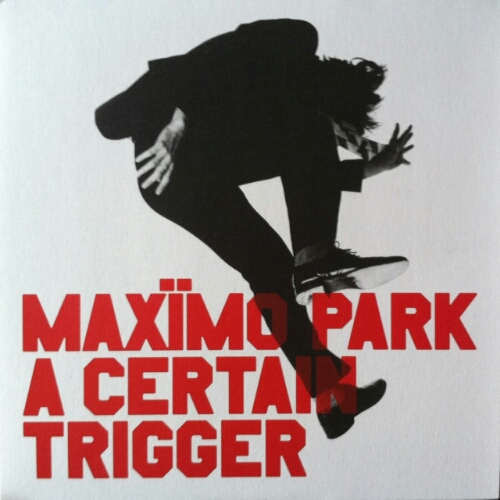

A Certain Trigger was released in May, but I don’t think I first heard it until July, maybe August. There was a great little review in Giant Magazine about it, and the cover struck a chord with me. All the music I listened to at the time was made by skinny dudes (often white) in slim fits and, whether I admitted it at the time or not, I longed to be so thin a good sized guitar could dwarf my frame. The only instrument I’ve ever played with any degree of competency was the cello in fourth grade, a fitting companion for my persistent hugeness. On the precipice of my twenties, I just naturally gravitated to the imagery of rakish Brits overshadowed by angular riffs and pulsing drum beats. Maybe there was something winsome in repetitive shots of handsome boys demurely downplaying their own appeal by shouting about sadness and swiveling their hips. (I was young and we’ve all held misplaced envy in our lives.)

Unlike the other post-punk, new wave revival bands I dug at the time, Maxïmo Park really sounded as awkward and rueful as their competitors pretended to be. They made catchy, resonant pop tinged with the kind of navel gazing sadness that really only makes sense when you’re eighteen. The kind of nebulous, ill defined rage at existence I felt at fourteen that helped make nü-metal a thing was now transmogrified into a needless sense of loss and solitude, so I was grateful for a band that seemed to only sing about girls that got away, nights that never ended, and staring into nothingness. The lyrical content was literate and mournful at times, but the sonics that propped up frontman Paul Smith’s warbled poetry possessed an infectious power that helped otherwise thin wisps of songs forge deeper connections with listeners willing to play the long game. I played it over Hollywood Video’s speaker system a lot less than Bloc Party’s Silent Alarm, but as time passed, this LP became an inseparable piece of myself.

“I’ll do graffiti if you sing to me in French…”

It’s provocative. Gets the people going.

Every song on the album, at face value, is more than a little doofy. The lyrics bridge the gap between “clunky, please god turn that off” and “how does he know what my soul tastes like???“, but the hooks land and the unorthodox structures provide an idiosyncratic pace that keeps things off-kilter. A song like “Graffiti” makes its worth known on first listen, but loopy and jagged tunes like “Limassol” are only skippable until the thirtieth spin imbues them with brand new life. There’s an event horizon with Trigger where what the average listener might brand as pleasant and forgettable begins to fuse with your very aura. For me, that Rubicon was passed when the fall hit.

I quit the video store, and all of my friends I had relished sharing the summer with had disappeared. I had dropped out of high school just before senior year, so once everyone graduated, there was this slim period when I could congregate with people I’d previously worried had forgotten me entirely. The summer was a time to pretend this snapshot would last forever. When everyone left for college in the fall, that crippling loneliness I dreaded came true. My life devolved into one long day with brief recesses of sleep. Living at home, being miles away from anyone I felt close to, I no longer felt like me. In that abyss, all I needed was A Certain Trigger, some kind of spark to break me out of this malaise.

I always had an easy time making friends, but now it was like there were no people. I couldn’t just talk to someone about The X-Men near the slide or impress a similarly malcontented chubby kid with my understanding of Cable’s origin. I had no friends to watch anime with after class. I was technically an adult and looked more like a grown ass man than usual, so it seemed harder to make new connections, as a lack of sun and never shaving made me look more like a serial murderer than a capable conversationalist. I had momentary excursions into social life where sparks of what I felt was my old self came alive but for the most part I got really preternaturally good at computer solitaire and read magazines. I don’t even remember masturbating much. I know that sounds weird, but when you’re so lonely you neglect your own dick it’s a new rung of sadness.

Not to sound like a Nick Hornby protagonist, but the music was all I had. The angular riffs scored a magical kind of loneliness I’d never quite experienced before. No more of the typical “girls I like don’t like me” shit every teen endures. In its place, a more frightening strain marked “high school is over and maybe the actual fucking universe doesn’t like me either.” I indulged so deeply in this album I began to feel like a goddamn Kieron Gillen comic long before I ever read Phonogram. It wasn’t the kind of obsession you get now, where you like an album so much you need to know everything about it. Despite being a top five dead or alive LP for me, I have spent so little of the ensuing ten years learning anything about the band. I mean, I know nothing about them. At all. Nor do I need or want to. I think they made such an impression because no preconceived notions poisoned my consumption of the music. It’s like Christopher Reeve being cast as Superman. You don’t bother getting distracted by some movie star’s distinct features. You just go along for the ride.

I am young and I am lost. You react to my reposte…

Who the fuck even talks like that? I did! In my head! Paul Smith’s torturously blunt lyricism was a-OK with me because it kinda made sense. His vocal delivery, bent and brittle, a nearly pathetic whine of mixed up vulnerability, was like a phonograph’s needle scratching against the pale desert of my dermis. I wasn’t cool enough to have The Smiths yet! That came later. Left to my own devices I finally had enough time for XTC, Wire, The Fall and all manner of others, but Trigger never left rotation.

Silent Alarm was better, but I could have fun to it. It reminded me of my friends, and I hated missing them enough to deny myself even the faintest hint of nourishing nostalgia. It hurt to reminisce but wallowing felt fucking great. I could tackle these thorny thoughts head on. No need to try to feel better. Just feel like shit all the time and you’ll tire of the darkness eventually, right?

I was confounded over how many of the album’s tracks centered around romantic loss, as I had no “her” to be reminded of at the apex of Smith’s wail. Just lonely nights writing shitty plays and horrible movies. Feeling dissociated from any and every thing. Getting transmissions from college life and feeling like you died early in a video game and your friends kept unlocking achievements. This is probably where alcohol started to make more than a cameo appearance.

Long before Drake positioned himself as the Bernard Herrmann of the Hitchcock movies that were my solo drinking nights, Trigger was the fuzzed out salve for every ailment life threw in my direction. In retrospect, the awful part is that nothing particularly bad was happening to me. My tragedy was that the life I was leading was one kept on the sidelines. I’ve had tons of failures since, and while it would be easy to romanticize this era in my life as “not as bad as it seemed,” it remains a purgatorial interlude I never want to repeat. A darkened, jaundiced kind of stasis. Passing furtive glances with pretty girls at Borders then immediately regretting it and hiding in a corner with a copy of Box Office Poison. Wondering how good I’d eventually get at being the shitty protagonist of every book I wanted to write. Around this time I was working on a whiny little screenplay about my situation and even though its narrative was a woeful one, the unofficial score Maxïmo Park provided offered a slice of catharsis. Lullabying myself to sleep with spiral notebook-bound dialogue I wished to share with people I barely had the fucking scrote to make eye contact with. I imbued fictive nonhumans with traits and experiences I wanted so badly to possess, hoping these flat little caricatures could teach me a thing or two about Not Wishing I Was Dead. It began as a frustrating process, but by laying those knotty feelings bare on white, lined paper, I gained a kind of perspective. It was easier to contrive solutions to my own problems when I freed them from reality and placed them in a safer environment. It wasn’t about playing God or exerting control. It was about being able to leave the tiresome confines of my own body and see things a little clearer. It was the addictive clarity Maxïmo Park’s music had afforded me (whenever I could stop beating myself up), only now it was my own art that was clearing the fog, not someone else’s.

That script sucked and I never finished it, but ten years on, the skills I was forced to learn with no one around to occupy my time still help me. The band followed up their debut with Our Earthly Pleasures, a more polished sophomore effort with better songs and stronger execution, but it was missing that aching hunger I fed on during those trying months until winter break, when getting to spend a few weeks with my friends helped remind me who I was.

Different sounds make sense at different points in your life. The pillowy, muffled drums of a Drake instrumental and the chugga chugga breakdowns of bands like A Day To Remember, though diametrically opposed, all had their time (2010-present & 2008-2009 respectively.) In 2005, the ponderous keyboard slides and post punk lament of Maxïmo Park did it for me in a way that helped make the hard times easier to digest. I haven’t cared for much of their output since, but who cares? I’ll always prefer their early work.