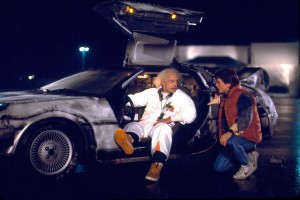

When I think of Back to the Future, the time-travel comedy that’s captivated millions of moviegoers since its release in 1985 (along with two surprisingly sturdy sequels in 1989 and 1990), I think about the “universal question” that Christopher Lloyd’s mad scientist Emmett L. “Doc” Brown asks in a pivotal moment in the series: “Why?” Why do these movies stay so fresh? Why did we all get it right, choosing to hold this brilliantly cast, flawlessly executed film in such high regard for our children and their children? Why is it so easy to get Christopher Lloyd to reprise Doc Brown in any advertising pitch? Why does nobody seem to remember (until recently) that Marty McFly went to the year 2015 (not 2013, not 2011) in Back to the Future Part II? And why is a good, entertaining, insightful book on the making of these films so hard to come by?

Like a picture fading and changing from a disruption in the space-time continuum, I now have answers to those questions, thanks to author Caseen Gaines, whose new tome We Don’t Need Roads: The Making of the Back to the Future Trilogy is required reading for BTTF enthusiasts, movie geeks, and anyone who just loves a good story. Gaines spent two years writing and researching this book, drawing from new interviews whose subjects include series creators Robert Zemeckis (writer/director) and Bob Gale (writer/producer); stars like Lloyd and Lea Thompson (Marty’s mother, Lorraine); Huey Lewis, contributor with The News of chart-topping soundtrack smash “The Power of Love;” and many more.

We Don’t Need Roads is essential to even the most dedicated fan. There were details in this book that eluded even this writer; Gaines’ extensive research on the bizarre five weeks of shooting where Eric Stoltz played Marty McFly instead of Michael J. Fox (NBC wouldn’t let Fox shoot a film concurrently with Family Ties) is worth the price of the book (it’s excerpted here), but Gaines digs so much deeper. And what really makes the book work is an impressive balancing act: Gaines doesn’t let the interesting minutiae (and there is a lot of it) compromise his goal of writing an informative book with a great story to tell—the story of how, against all odds, Back to the Future was made and continues to entice new audiences, time after time.

Gaines, also an English teacher and theatre director in New Jersey, was kind enough to discuss the book and his creative process with Deadshirt at length. Fasten your seatbelts: You’re about to read some serious shit.

Early in the book you talk about your own introduction to Back to the Future as a child. When did a book seem like a viable idea?

Like every Back to the Future fan, I’ve been waiting my entire life for 2015. As the date approached, I was surprised that no one had written a comprehensive book on the making of the trilogy. Not only because Back to the Future is a really important franchise to the culture, but there’s a really interesting story as to how these films were made. When you talk about Eric Stoltz originating Marty McFly but [being] replaced with Michael J. Fox; Crispin Glover not returning for the sequels; the fact that Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale, at this point in their careers, did not have a substantial hit until this film becomes a huge phenomenon—all of these things were very interesting to me, and I wanted to do my part to help preserve this history in anticipation of the 30th anniversary, when I anticipated there would be a great deal of attention on the films.

You touch on it throughout the book, but, for our readers who’ve not had the opportunity to read, what is it, do you think, that makes Back to the Future so universally popular? This is a cross-generational thing, and I don’t think I’ve experienced anything like it in my lifetime.

Back to the Future is one of the greatest ideas in recent memory for a film: Make a teenager accidentally go back in time to meet his parents as teenagers, which threatens his own existence. That’s a fascinating idea, [but] Back to the Future is also a really well done movie, when you consider all the complications making it. It’s technically fantastic—everything looks great, there are very few shots in the film that are regrettable. (laughs)

But, at its core, Back to the Future is also a film with a lot of heart: about a teenager growing to appreciate his parents, and a couple that has fallen out of love reminded why they got together in the first place. It’s a film about relationships and friendships and people, and because the characters are so strong, we’re still talking about it for 30 years. If it were just a great science fiction/special effects film, I don’t think it wouldn’t have endured…but it’s a film that’s tender and sweet—almost surprisingly so, given the science fiction elements of the story.

It’s almost like the original Planet of the Apes franchise in that regard: it’s science fiction, and it seems like just a generic popcorn movie, but [there’s] a lot going on in terms of the interpersonal relationships of the characters.

Were there any people you wanted to interview but didn’t? Of course, Michael J. Fox comes to mind, but were there others?

I didn’t get to speak to Eric Stoltz or Crispin…Michael J. Fox, that came down to scheduling; he was in production on The Michael J. Fox Show, and we couldn’t find the right time.

But there are so many stories in the book. I think I did about 500 hours of interviews, and the first draft I handed in was an extra 100 pages. We had to scale it back so it wasn’t a brick in someone’s pocket. (laughs)

There’s such a great, great history and so many fantastic people worked on these films. It’s a point of personal pride to be able to reintroduce people like Kevin Pike [visual effects supervisor], Michael Schiffe [construction coordinator for the DeLorean], Rick Carter [production designer of Part II and Part III] or John Bell [visual effects art director for Part II and Part III], people who are not household names but made huge contributions to these films. It’s good to remind everyone that these films are more than just Bob Zemeckis or Michael J. Fox—it was really a team effort and [the films] are so successful because everyone was operating on all cylinders.

What I really love about this book is your ability to balance your perspective as a fan and a storyteller. This book is full of details that even the most hardcore fans (myself included) don’t know. But it is also a narrative success: any “level” of fan can get into this. Can you discuss your writing process as it pertains to this challenge—not letting the fandom get in the way of the story?

For me I was very mindful of two things. First, you always have to shoot for the middle in terms of fandom. My goal is someone who has watched the films a million times should be able to read this book and learn something new. But also if you’ve watched the film in the last 10-15 years on TV, or you remember watching them in a theater but haven’t thought it that much—maybe you only think about it every time someone tries to create a hoverboard—if you’re a more casual fan, you should also be able to read and be filled in on everything you don’t know. There are people, and it’s surprising to me, but there are people have read this book and didn’t know Eric Stoltz was originally Marty McFly. Those people are shocked, and the entire story becomes additionally fascinating. For someone like you or I, you know Eric Stoltz does not play Marty McFly, so for those readers, I tried to make it less about what happened and more about the process behind it.

Second, I was very aware that this book would only be successful if it was a story about people. We Don’t Need Roads is the story of Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale, not DeLoreans or hoverboards or how many tickets were sold. It’s about two wannabe filmmakers who met in college, made films that weren’t commercially successful, had an opportunity with Back to the Future, had a ton of obstacles making this film, and it changed their lives forever. To me, it was always the story of these two Bobs. And as a character-driven story, my goal was for it to read like a novel.

We Don’t Need Roads goes into detail on aspects of the series that fans have only been able to speculate on or know about in part—the presence of Eric Stoltz as the original Marty McFly, Jeffrey Weissman’s troubled status as Crispin Glover’s replacement on Back to the Future Part II and the accident on the Part II set that seriously injured a stuntwoman. As a writer and researcher, what are the secrets to effectively uncovering stories like these?

I think it’s about trying to always be aware of the big picture—what do all these pieces mean? For me it’s not about “dirt,” it’s almost the opposite. Crispin Glover’s eccentricities and Eric’s complications on set—the fact that they were still able to make three fantastic films just makes Back to the Future a more impressive film franchise.

I find that you avoid the questions you really want to ask at your own peril, and the peril of your own work. Any time I ask someone a question that I’m afraid will make them uncomfortable, I always get a better answer. Because people want to talk about things they haven’t spoken about before. Having an hour of Christopher Lloyd’s time and wondering if he’ll want to talk about certain things…he wants to talk about Eric Stoltz and Mary Steenburgen. How many times can he answer what it was like riding in the car? These stories came out because, in some aspects, it was the first time people had been asked about certain things. Which is sort of crazy, when you think about it!

I agree, especially in the age of DVD documentaries, where actors are interviewed about these roles. I’m glad you mentioned Christopher Lloyd specifically—you think about the last five or ten years, it doesn’t seem to be much of a trick to get him to play Doc. Of course, it helps to add authenticity, but it’s not something he may need to do.

Christopher Lloyd was a fascinating interview for that reason. He remains in love with these films and Robert Zemeckis as a filmmaker, and [feels] so fortunate not only to play Doc Brown in the films, but to keep being invited to play Doc. He has such fond memories of playing this character and loves getting that phone call. When I spoke with him I was worried if he’d be forthcoming about being Doc, and it was so great to be reminded in speaking with him that he’s a fan of these films. It’s such a cliche for an actor to say that, but he really is. In the book, he says he’ll stop and watch Back to the Future if he ever finds it on television. He really does love it.

Were there any aspects of the series that you would have liked to go into greater detail on? Thinking about those aspects that the other book might cover, or some of the things that had to be cut from your book—have you thought of putting some of it online, as your own “DVD extra”?

Yes, actually. I did interviews with people who worked on the animated series and the ride. But you get a word count. The book originally came in at maybe 25% greater than its word count. Over the course of editing, the book is still greater than the word count requested, but there wasn’t anything more we could or want to cut. But there’s still close to 100 pages we cut, mostly about things that did not deal with the films itself. The last chapter of the book, “Your Kids Are Gonna Love It,” is sort of a catchall chapter. It talks about The Michael J. Fox Foundation, and merchandising, and the animated series, and the ride—that section easily could have been two or three chapters instead of one. Also, there were some great stories from the making of the sequels that we trimmed—I am hopeful that we will release these things online, because it’s all written!

Maybe we’ll release it closer to October. We initially were going to have the book come out around then, to hit the “future day,” but then we thought to get ahead of the anniversary of the first film in July. It was a lot of work—we had to move at 88 miles per hour to do it—but we did it! So much of a focus gets put on Part II, living in 2015, so it’s nice to be on time for the 30th anniversary of the first film and remind people that the first film, in and of itself, would have been special even without the sequels.

We Don’t Need Roads is, top to bottom, a labor of love. What advice do you have for anyone looking to execute the same type of passion projects? This is particularly worth asking as you wear several hats when not writing, namely teaching and non-profit theatre.

Embrace what makes you unique, and don’t be afraid to work for what makes you unique. All my life, as a fan of Pee-Wee Herman you get a lot of unsolicited opinions about Pee-Wee Herman. I love that character and that world and so much of my creative sensibilities come from watching a little bit too much Pee-Wee’s Playhouse as a kid. But when you have the ability to write a book about Pee-Wee Herman, you realize all those years of being “the weird kid” paid off! I embraced it and knew it was important and knew there were other people like me who still loved that character. People ask how I got so many people to talk in this book. The answer is I called, and I asked! You can’t be afraid of doing that.

I often think about this moment where I developed this “let me just try and go for it” attitude. I was watching MTV at an age where I was probably too young. Batman Forever was coming out, and they were talking to Seal for a special. He was asked how he did [“Kiss From a Rose”] and he said something like, “Well, I’ve always been a fan of Batman, and I called up Warner Bros. and asked if I could contribute a song.”

Now as an adult, I know that story is completely ridiculous—Seal is on Warner’s label, and there was probably more than serendipity that made that happen. [Additionally, “Kiss From a Rose” first appeared on Seal’s second album in 1994, a full year before Batman Forever was released. -MD] But I always believed as a kid that you could call and ask to do a soundtrack song and they might just say OK! I think a lot of my gumption in that regard comes from my completely childish misreading of this Seal interview! (laughing)

With the book available and (hopefully!) by all accounts a success, what’s next?

I am currently working on a dual biography of Ray Bradbury and Ray Harryhausen. They were lifelong friends, born and died within months of each other. They knew each other their entire lives and loosely collaborated together on The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, and together changed the landscape of science fiction. The book is in its very early stages, but it’s looking not only at both of them as individual players in the science fiction genre but also how their friendship shaped their contributions to their work. It’s similar to the other books I’ve written, but there’s a different scope—and for me the hook is, when you look at what will undoubtedly be the two highest-grossing films of the year, Jurassic World and Star Wars: The Force Awakens, those are two films that would not have existed were it not for Ray Bradbury and Ray Harryhausen.

Right hand on your book manuscript…which is your favorite of the trilogy?

Part II is the most interesting and might be my favorite, but Part I is the best. Robert Zemeckis, in the book, says Part II is one of the most interesting movies he’s ever made, and I agree. It gets a lot of points for being ambitious when it did not have to be. That movie would have done completely well if they had done a lazy sequel, and they refused to do it.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TkyLnWm1iCs&w=560&h=315]

If you had a working DeLorean, when and where would you travel to? (Assume that, like in the Saturday morning cartoon, your DeLorean has also gained the ability to travel through space as well as time.)

I would travel to the 1970s and I would stay right where I am, in the New York area. Live my own Saturday Night Fever! (laughs)

Does your love of Back to the Future extend into collecting? Any favorite items?

I’m really into fan art! A really great artist named Rich Pellegrino does these beautiful portraits of pop culture figures, and I have two beautiful framed prints of Marty McFly and Doc Brown. Right now, my most prized possession is definitely my copy of the book—I’ve been collecting signatures from people who worked with me and the films. When I get Eric Stoltz to sign it, I’ll know I’ve made it!

Back to the Future Part II predicted a version of 2015 I wish were note perfect. What’s the one thing from the movie that you wish were in the real 2015?

I’m going to ignore that question and answer with what I’m glad does not exist: I’m glad that we do not have flying cars. Every time I see an accident I’m glad it’s on the ground instead of two cars falling on the pedestrians walking down the street.

Maybe I’d like the clothing that adjusts to your body. I hate clothes shopping, so I could get a nice baggy shirt and zap it around my body so it could fit.

The thing everyone forgets is all the years in the movies end in “5.”

People are fanatical about different things. I give people a pass when they don’t know, but how easy is it to Google the date and fact-check it? It’s like Old Biff says: “You sound like a damn fool when you say it wrong!”

You can buy We Don’t Need Roads: The Making of The Back to the Future Trilogy here.