When Joel and Ethan Cohen’s 1996 film Fargo was first released on VHS, PolyGram Video produced two little promotional items that perfectly encapsulated the film’s bloody, sour take on Midwestern domesticity. These items were a pair of snowglobes recreating two of the film’s most memorable scenes: police chief Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand) examining the body of slain state trooper, and Marge cornering brutish killer Gaear Grimsrud (Peter Stormare) as he feeds a severed leg into a wood chipper. If you shook the snowglobes, bloody red snowflakes would fall over the tiny people inside. It’s easy to imagine the snowglobes as part of the film’s set design, scattered among the kitschy pig figurines in the Lundegaard home or the Arby’s wrappers in Marge’s office, as long as you don’t look at them too closely. Murder became a tchotchke.

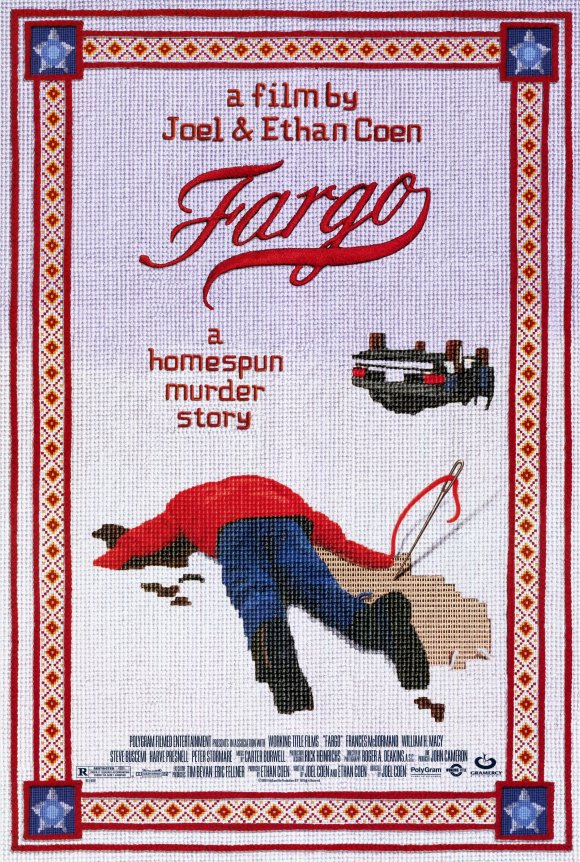

When Joel and Ethan Cohen’s 1996 film Fargo was first released on VHS, PolyGram Video produced two little promotional items that perfectly encapsulated the film’s bloody, sour take on Midwestern domesticity. These items were a pair of snowglobes recreating two of the film’s most memorable scenes: police chief Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand) examining the body of slain state trooper, and Marge cornering brutish killer Gaear Grimsrud (Peter Stormare) as he feeds a severed leg into a wood chipper. If you shook the snowglobes, bloody red snowflakes would fall over the tiny people inside. It’s easy to imagine the snowglobes as part of the film’s set design, scattered among the kitschy pig figurines in the Lundegaard home or the Arby’s wrappers in Marge’s office, as long as you don’t look at them too closely. Murder became a tchotchke.

Fargo is a film about conniving, violent, petty people, and the sad misunderstandings that can happen when relationships are left to curdle like old milk. The film opens with car salesman Jerry Lundegaard (William H. Macy at his most milquetoast) arranging the kidnapping of his wife so that he can collect a ransom from his wealthy father-in-law to pay off an encroaching debt. The kidnappers, partners Carl Showalter (“funny-lookin’’’ Steve Buscemi) and the blank-eyed Grimsrud are instantly the worst people you’ve ever seen in your life. When Lundegaard joins them, the trio bicker pointlessly about the meeting time—7:30 or 8:30?—and Showalter struggles to understand why Lundegaard wants to ransom off his wife instead of simply asking his family for the money. Lundegaard stammers out non-explanations, and it immediately becomes clear to the viewer that these men are completely incapable of communicating with each other, and are already in over their heads. The characters and their plans are so pathetic that even when the violence in Fargo is unpredictable, it seems strangely inevitable.

The Lundegaard home is a model of Rockwellian normalcy until they’re destroyed by Jerry’s wretched veniality. Wife Jean is introduced as a frizzy-haired, pink sweater-clad homemaker, perpetually chopping vegetables or furiously stirring a mixing bowl. (During the kidnapping, Jean literally becomes trapped by her own domesticity as she accidentally ensnares herself in her shower curtain while fleeing and falls down the stairs.) Does Jerry Lundegaard love his wife? Her picture adorns his desk and she greets him with a chirpy, Minnesotan “Hi, hon!” but whatever affection that once connected them has faded in the shadow of Jerry’s resentment of his overbearing father-in-law, Wade Gustafson (Harve Presnell). William H. Macy’s exaggerated “Minnesota Nice” accent is so comical that we almost forget he’s a monster, and that he’s not even endangering his family out of a misguided belief he’s protecting them. Gustafson states that Jean and her son “never have to worry” about money; Lundegaard’s massive debt is a danger only to himself. But already despised by his steely father-in-law and regarded as a mealy-mouthed liar by his customers, Jerry cannot stand one more exposure of his weakness and jeopardizes Jean as a deliberate “screw you” to a man who sees right through his empty smiles. By using his wife as a pawn, Jerry sacrifices one of the few people who actually still cared about him.

Jerry’s son Scotty, a boy on the precipice of bratty teenagerdom, is thrown back into the vulnerability of childhood after his mother is kidnapped, and we last see him clinging to a stuffed animal as Jerry fails, both as a father and as a human being, to console him. Whenever I watch Fargo I spare a few moments to think about that poor damn kid, and the horrible future awaiting him after his mother and grandfather are killed, and his father is arrested. Wade Gustafson promised that Jean and Scotty would be taken care of, but the film ultimately obliterates that sense of safety. Lundegaard destroys his own family, and his innocent son is cast into limbo. Fittingly, the last we see of Jerry as he’s being arrested is his impotent attempt to escape a bathroom window, as Jean did earlier in the film; she could not escape her sad end, and neither can he.

The mismatched pair of Showalter and Grimsrud represent a partnership at its most bitter and decayed. It’s never made clear how the men met or how long they’ve been working together, but their petulant squabbling over pancake houses and Grimsrud’s long silences are like the most frustrating, friendship-straining road trip you’ve ever been on. (At a lean 98 minutes, Fargo is ruthlessly good at giving the audience only what they need, and leaving all extraneous information buried under the snow with Gustafson’s money-stuffed briefcase.) They share everything, from a motel room where they have mechanical sex with prostitutes, to the kidnapping itself, and their parasitic relationship becomes a different kind of domestic hell when they take Jean to a tiny, tree-shrouded home to wait for the money.

Fargo is a very funny film punctuated by staccato bursts of violence, mostly at Showalter and Grimsrud’s hands, and their victims are innocent people who were in the wrong place at the wrong time (the motorists who witness Grimsrud killing a cop), or were caught up in something they never understood (poor, perpetually wailing Jean). The ugly pointlessness of the deaths is amplified by Grimsrud’s hulking, mostly silent demeanor; he seems at times to be barely human. When Showalter returns to the hideout to find Jean murdered (offhandedly, offscreen) and Grimsrud eating cereal and watching television, what we expect to be another scene of comically off-kilter banter ends with Grimsrud cutting Showalter down with an axe. It’s probably too easy to compare that final fight over a tan Cierra to a short, brutal divorce, but it’s a separation as sure as Showalter’s leg is bloodily separated from his body.

The Coens invite us to laugh at the patheticness of these characters, whether it’s Showalter’s weak exclamation of “Oh, Daddy!” or Jean’s clumsy, blindfolded attempt to escape in the snow, but they treat their heroine, Marge Gunderson, with the utmost respect and sincerity. Amidst the violent chaos Lundegaard and the kidnappers inflict on others, Marge, with her folksy demeanor and canniness as a police officer, is a promise of order and rightness in an unpredictable universe.

Marge is introduced surprisingly late in the film, but once she’s on screen it’s impossible to look away from her (and no, that’s not a crack at her being seven months pregnant). We meet Marge and her husband, the aptly-named Norm, on a groggy but blissful morning: Marge is called in early to investigate a triple homicide, but Norm gets up to make her eggs before she leaves. The subversion of expected gender roles is easy to spot: Marge is the dedicated cop, and painter Norm is the spouse who brings her Arby’s for lunch. As a couple, Marge and Norm are so tender and kind to each other that no litany of yah-you-betcha’s can reduce them to cartoon characters. Part of the pleasure of watching them is knowing that they’re perfectly average people who paint mallards for postage stamps and watch documentaries about bark beetles. There’s nothing small or pathetic about the Gundersons; their warmth permeates what could have been a strangely chilly, brittle film. When Marge tells Grimsrud that “it’s a beautiful day,” the all-encompassing wintery whiteness that surrounds the police car on the road suddenly seems less frightening and obliterating. We believe that it is a beautiful day, because Marge says it is.

It’s significant that Fargo doesn’t end with Marge driving Grimsrud to justice, telling him there’s more to life than a little money, or even with Jerry Lundegaard’s undignified arrest. It ends with Marge and Norm at home, cuddled in bed together, contentedly musing on the two months ahead before the birth of their child. Fargo is a dark comedy, as kitschy as a corpse in a snowglobe, and full of petty, greedy people who sell their wives or kill their partners and say “oh jeez!” in the same breath. But there’s genuine love, too, and basic human decency, if you know what’s really important in life. You betcha.

Wow, that’s a really clever way of thkniing about it!