By Dominic Griffin and Max Robinson

When it comes to action franchises, Tom Cruise’s vanity project, the four film deep Mission: Impossible series, is a unique beast. Loosely (and somewhat controversially) based on Bruce Geller’s beloved television series, the first film hit screens in 1996, immediately making an impact on popular culture based solely on the strength of the Lalo Schifrin’s repurposed theme music, Tom Cruise’s as-yet-unfrightening smile, and that easily parodied and frequently plagiarized sequence in which Cruise’s special agent Ethan Hunt is lowered into a room by a wire.

What’s fascinating about this franchise is it’s mutability. A bevy of heavy hitting screenwriters have each had their hands in scripting Hunt’s adventures, and each installment is helmed by a drastically different filmmaker, each with their own specific style that they bring to the table. The only real constant is Cruise himself, a reliably functional American movie star whose dedication to outrageous stunts and an unwavering intensity more than makes up for a limited range of on screen emotion and IRL batshit insanity. The product is essentially the same (a straightforward, spy-fi action thriller) but the delivery system shifts in tone and execution. It might be the closest thing American cinema has to the Bond franchise, if in it’s own backwards, curiously charming way.

Mission: Impossible (1996)

When we first meet Ethan Hunt, the quintessential Tom Cruise protagonist, he’s working for IMF, the franchise’s spy organization, in a unit with Jon Voight (here, playing Jim Phelps, from the original television series) that is rounded out by a coterie of international actors and for some reason, Emilio Estevez, who turns in the action movie equivalent of Drew Barrymore’s performance from Scream. Phelps’ unit works a mission that goes awry, leaving the entire unit, save for Hunt himself, dead or missing, leading IMF to think him a traitor and a mole. The (obviously) wrongly accused Hunt has to work out who the real mole is, clear his name, and beat the bad guys. There’s the requisite twists and turns, and a villain reveal that disenfranchised any remaining fans of the source material, and some largely satisfying action/suspense sequences, namely the aforementioned scene of Cruise being lowered into a hypersensitive server room.

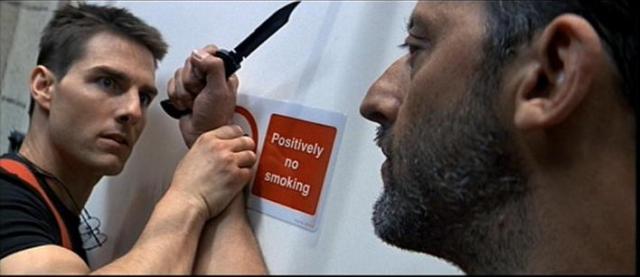

Brian DePalma, something of a redheaded stepchild of the 70s American auteur movement, was the first director to put his stamp on this series. Under his guidance, and what we can only imagine to be a lot of creative input from Cruise, as this was his passion project, DePalma crafted a smart, classical action film that creates a timeless quality often foiled by it’s hideously 1990s nature. Working from a patchwork screenplay from Steve Zaillian, David Koepp and Chinatown scribe Robert Towne, DePalma chooses to experiment with long take camera movement and POV shots that would later serve him better in Nicolas Cage’s Snake Eyes. Using canted angles in an artful way helped refine the film’s pulp leanings, adding a touch of grace to the proceedings. Unfortunately, many of the film’s key scenes rely on the use of computers, and to say that the filmmakers handle the burgeoning information superhighway with slightly more aplomb than the people behind Hackers is really the best that can be said on the subject.

What begins as an attempt at timeless suspense cinema ends up grounded viciously in the relative tackiness of the 1990s. The film’s plot machinations and third act desire to ratchet up the explosion factor ends up being its own undoing, distracting from the rest of the piece’s otherwise virtuosic use of film technique to modernize and optimize an aging television property for the big screen.

Mission: Impossible II (2000)

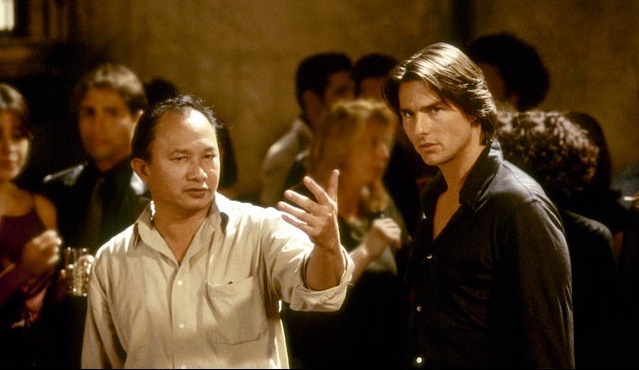

Four Years later, Cruise returned to the franchise with acclaimed HK action director John Woo in tow. Woo, whose American forays into the genre, Broken Arrow and Face/Off, are beautifully realized trash epics, seemed perfectly suited to bring Mission: Impossible into the new millennium. This being the first to follow The Matrix, the move to more overt gun violence and black clad spies wasn’t a surprise, but the film definitely represents an unfortunate tipping point in Woo’s films. You see, the balletic gun fights and artful slow motion and reckless use of doves are all pockmarks of Woo’s style that, when used in moderation, are like a thin layer of cake frosting. MI-2 represents what I will refer to as The Full Woo, where that thin cake frosting layer is replaced by a drunk, three hundred pound man asphyxiating on whipped cream.

Ex-Star Trek writers Ronald D. Moore & Brannon Braga get story credit on this film, with Robert Towne returning to pen the actual script, but let’s get one thing straight: Ben Hecht wrote this movie fifty years earlier, except he and Alfred Hitchcock chose to call it Notorious. From my understanding, John Woo had already envisioned a number of set pieces for this film, and the writers, for lack of a better option, had to write around what he wanted to shoot, which is not entirely uncommon in the world of tentpole blockbusters. What is a little uncommon, is shamelessly ripping off one of the greatest spy thrillers ever made by human hands.

Ethan Hunt is back, rock climbing with longer hair and looking equally charming and intense. Anthony Hopkins, in a thankless cameo as Hunt’s new handler, puts him on a mission to stop Dougray Scott’s pale imitation of 006 from Goldeneye, using his ex-girlfriend, Thandie Newton, as bait. It’s an unsubtle, Maxim magazine looking, Axe-scented inversion of the Cary Grant/Ingrid Bergman/Claude Rains triangle from Notorious, but the stealthy stagecraft Hitchcock employed so well is bluntly replaced by slow motion car chases that look like sexually charged Revlon ads, motorcycle face offs that seem like Playstation cut scenes, and a fundamental misunderstanding of interpersonal interactions. As a film, it functions surprisingly well, despite the threadbare plot being a faulty Jenga tower of MacGuffin cliches, but it’s Woo’s decision to dramatize even the most throwaway moments that exhausts the audience.

The actual action scenes are fun and exciting, but they feel less so when meet cutes and awkward reunions are framed and staged with the same sense of Herculean bombast as the film’s climax. Hitchcock always considered drama life with the boring parts cut out and melodrama to be drama with the boring parts cut out, but under Woo’s hand, MI2 is just a salad with the leafy parts cut out and replaced by chocolate covered bacon.

– Dom

Mission: Impossible III (2006)

MI-3 marks the point where the franchise transitions into being this strange little try-out area for directors established outside of film. This is JJ Abrams’ directorial debut and if the Mission: Impossible films truly are the American equivalent of the Bond franchise, then MI-3 is its Never Say Never Again. This go around, Ethan is retired from field work but is brought back into the game after his protege (Keri Russell in the kind of cameo that we’ve come to expect from the series) is abducted and killed.

One of the truly interesting things about the Mission: Impossible series is how each individual film feels like a snapshot of that particular period of time in Hollywood. The original film is very much in the vein of Goldeneye, which came out the prior year, while MI-2 is the excess of films like Woo’s Face/Off turned up so hard the lever snaps off and the sirens start blaring. In that sense, MI-3 comes from the sort of antiseptic action environment that gave us The Bourne Supremacy and Abrams’ TV spy drama Alias.

When we talk about Mission: Impossible III, what we’re more than likely talking about is Philip Seymour Hoffman’s turn as unflinchingly amoral arms dealer Owen Davian. There’s no movie without him; he’s easily the strongest villain in the franchise and he’s the only actor in the series who can match and even surpass Tom Cruise’s onscreen gravitas. Davian, like future Abrams’ movie bad guys Nero and Khan, isn’t especially complex but he leaves one helluva impression.

The proceeding films in the series hinge on a big action set piece, Ethan suspended inches over the floor or flying through the air amidst doves. The biggest indicator of how Abrams’ sensibilities as a director diverge from his predecessors comes in the scene where Ethan interrogates Davian aboard an aircraft. Abrams opts for a brief but haunting exchange-turned uncomfortable Patriot Act interrogation between two guys that viscerally hate each other’s guts. The scene’s so amazing that the carnage-filled bridge sequence that follows almost feels like a let down.

Given the somewhat unenviable job of serving as a palate cleanser after its style-heavy predecessors, Abrams’ Mission: Impossible entry is a competent if occasionally dry action movie that really shines in its third act (with a neon-soaked Hong Kong showdown that predates Skyfall by six years, no less!).

Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol (2011)

All thriller and no filler, Brad Bird’s turn at the wheel isn’t just the best Mission: Impossible movie, it’s the best action movie of the last twenty years. Ghost Protocol feels like a calculated recalibration of the entire franchise, a PhD dissertation on the state of the American actioner from a Die Hard scholar. No small feat considering it’s Bird’s first live action film.

The Mission: Impossible films have always been action delivery mechanisms; Bird understands this and wisely builds the story around his set pieces. That doesn’t sound like it should work but it does; there’s just enough story to keep you involved between chases and explosions. The things that worked in the older films stay, like a storyline that throws Ethan Hunt and team out into the cold after they’re framed, and ditches the stuff that doesn’t (Bird evidently doesn’t care for the storytelling cheats IMF’s experimental spytech provides because it constantly breaks.)

All of this speaks to a larger point; this is a movie made by someone who understands stakes. And no scene in the movie demonstrates this better than Ethan Hunt’s climb up the side of the Burj Khalifa. As Ethan’s high tech wall crawling gloves fizzle out mid-ascent and he’s forced to improvise how he’s going to reach the computer control room several stories up, we realize he doesn’t even know how he’s going to get down. It’s tense, it’s funny and somehow you’re tricked into thinking Tom Cruise can die here, even if it’s just for a few seconds. In other words, it’s flawless.

While the first three Mission: Impossible films felt like part of larger waves of like-minded blockbusters, Ghost Protocol comes across as an attempt to establish the new rules. Although it’s aesthetically a throwback to the kind of cold war spy thriller the original series was, Bird’s film is practically post-modern in how it lays the fundamentals necessary to making great movie action on the table for all to see.

– Max

I refuse to merit John Woo’s MI2 as Woo’s original directors cut was 3&1/2 hours!! Paramount and Cruise told Woo it couldn’t be more then two hours. Paramount brought editor Stuart Baird who took out a whopping 90 minutes!!! A who movie within itself!! Visually Woo’s film looks the slickest from the other three. I need to see the 3&1/2 hours directors cut as I suspect it’s short of a masterpiece. Major set-pieces were taken out and the violence reduced from an R to PG13. It’s time to release the directors cut on home entertainment!!