If you’re not a wrestling fan, closeted or otherwise, seeing the hashtag #WWENetwork pop up all over the social media stratosphere for the last few weeks must have been pretty confounding.

Not unlike most religions, megalomaniacal promoter Vince McMahon’s personal vision for what he calls “sports entertainment” is a difficult commodity to understand if you didn’t grow up with it. If you love wrestling, it’s nigh impossible to fully express the joy it can bring when done right, with its compelling mixture of cartoonish character acting, improvisational action choreography and years-long continuity. If it’s not your cup of tea, no cleverly written think piece in the world will help you stop side-eyeing your friends who obsess over it.

Somewhere in that troubled chasm between professional sports and avante-garde theatre, World Wrestling Entertainment exists as a global entity without peer. Throughout the mid-nineties, McMahon’s empire was at constant war with their distinguished competition, World Championship Wrestling, backed by Ted Turner. The prime years of the so called Monday Night Wars, from about 1997 to about 2001, are referred to as the Attitude Era, a point in time wistfully longed for by most wrestling fans for its violent, boundary-pushing, and sexually charged content.

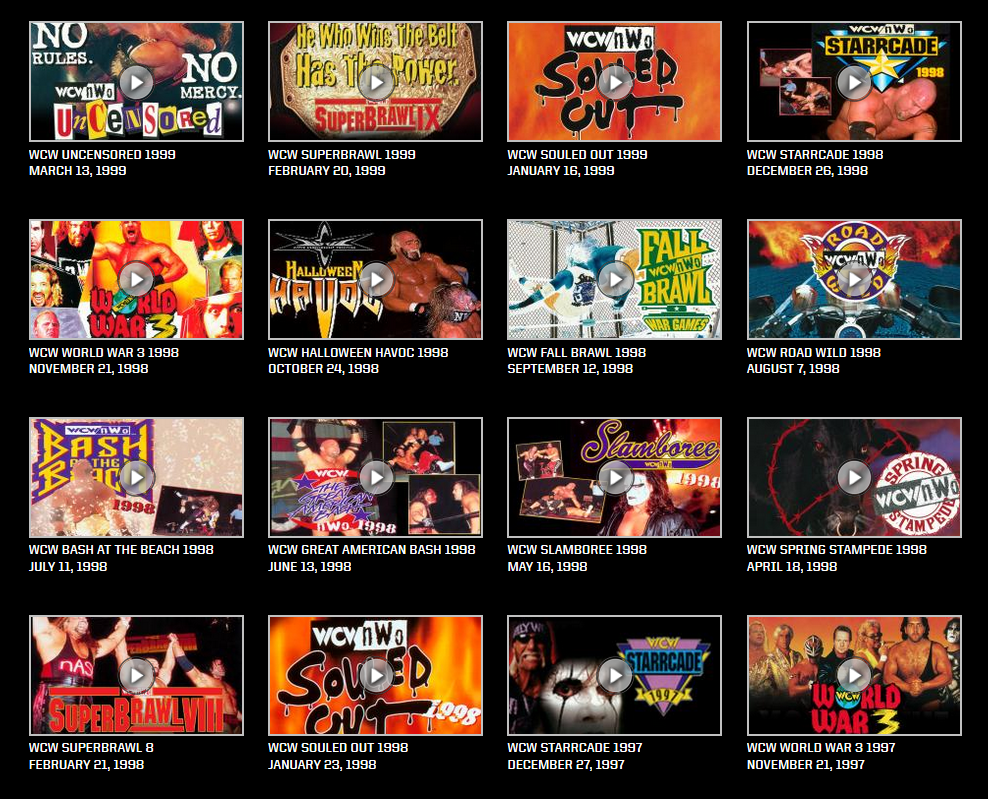

When WCW fell on hard times, Vince McMahon bought out his enemies, assimilating their product, and an extremely lucrative tape library, into his own. You would think such a victory should be celebrated, but imagine what comics would be like if DC had bought Marvel when they went bankrupt in the nineties, or if Universal was the only major studio producing movies. With practically zero realistic competitors in their path, the WWE needed a new ceiling. Being alone at the top led to indulgent, self-defeating storytelling and a lot of fans checking out when the product deftly moved from TV-14 to TV-PG, courting a new generation of kids to replace the ones who became so jaded. With his wife determined for a career in politics, McMahon was no longer content with running the biggest wrestling promotion on Earth. They needed to become a global entertainment force.

See how that video has nearly no images of blood, or breasts, or grown men chopping their crotches? Make-A-Wish, Totino’s Pizza Rolls, movies, Scooby Doo, Twitter. WWE has managed to give themselves a semi-convincing facelift, positioning themselves as powerhouse content creator, Disney with body slams. A network was just the next logical step for the brand. Pitched as “Netflix for wrestling,” (presumably because “Having a channel on an actual satellite/cable provider was too difficult, logistically” proved too wordy) the WWE Network’s front is two-fold; one, a 24/7 streaming channel accessible by the WWE website or its mobile app, and two, a massive, on-demand library of its content from the last fifty years, not to mention all of the content it’s acquired from other slain/bought out competition. For $9.99 a month, you get all that, and access to every monthly pay-per-view event the company runs when they air, including Wrestlemania, which normally goes for $70 by itself.

Yeah, that’s why everyone you know who owns at least one “Stone Cold” Steve Austin shirt has been collectively losing their shit.

It’s a great deal, and there’s a mountain of video to consume. I got The Network the morning it became available and it was all I watched for four days, at home, on the bus, on my lunch break, in bed. Even with the streaming difficulties and the realization that some of the promised old events were missing, there was just so much to like that I couldn’t care less about the criticisms. Because I’m an omnivorous and easily distracted media obsessive, it was on the fifth day that I was “Netflix scrolling” myself to bed, unable to choose between Starrcade ’95 and Wrestlewar ’92 as lullaby flashback trips. I’m totally in the bag for The Network, and would have signed up for a “lifetime subscription” if such an option existed, but I’ve found myself more interested in what this “game changer” says about the artist (McMahon) and their audience (the fans.)

Wrestling, not unlike mainstream superhero comics, exists in an ongoing “universe” with a colorful cast of characters, and an ever-mutable status quo. Fans can follow a wrestler through multiple gimmicks and allegiances and fantasy-book-long narratives to fill in the inevitable plot holes that arise on a show written by out-of-work soap opera scribes. If you think the Supernatural/Doctor Who/Sherlock fandom is a bit much, you’ve obviously never read any Randy Orton fan fiction. By laying all of that history bare, The Network makes it even easier to see that long lineage as what Rust Cohle might refer to as a flat circle. The sort of fan theorizing and active engagement of the viewer engendered by Lost or True Detective happens in wrestling, but rarely is it actively encouraged. Loki may be the villain in The Avengers, but if the audience want to root for him, they can. On screen, the WWE pretends to support their fans’ freedom to boo and cheer whoever they like, particularly during segments starring wrestlers the creative team wants to be cheered being courted by nothing but boos. It’s just passive aggressive crowd control. Instead of democratizing the fandom experience, something this service is uniquely poised to do, it has other concerns.

The Network, from WWE’s perspective, is a conduit to relive the promotion’s greatest moments. All of the advertising is centered around the idea of going back to Wrestlemania I or seeing the first Royal Rumble, something I think statistics would show very few subscribers really felt like doing. The beauty of looking back in wrestling is reliving the moments that were important to YOU, not to the corporation that birthed those moments. The first thing I wanted to relive was Owen Hart pulling an upset victory over his brother Bret in the opening of Wrestlemania X. My girlfriend couldn’t wait to watch Bash at The Beach ’96, to see Hulk Hogan’s villainous heel turn. If Vince McMahon had his way, we would all be watching an endless loop of WWE produced documentaries recounting the history of the business and how his ruthless savvy took him to the top.

A vast majority of the non-wrestling content of The Network is exactly that, history written by the victor. In between VH1-esque talking head countdown shows and ESPN-aping “pre-shows” for flagship programs Raw and Smackdown, old WWE Productions exploring its history seem to reinforce Vince’s genius above all else.

Even one of the biggest promises made by The Network, that all content would air completely uncensored (obviously a ploy to win back Attitude Era fans), was broken. One might expect some measure of censorship from an organization trying very hard to stay family friendly when its history includes one of its current authority figures dry humping a corpse. It’s not so much the sex and violence that are missing as much as the little blemishes. A hilarious match between Shawn Michaels and Hulk Hogan from Summerslam ’05 (which I attended live) is trimmed to lessen the effect of Michaels openly mocking Hogan’s entire career. Perhaps because the Hulkster recently returned to shill The Network itself? Tons of infamous “shoot promos” (planned moments of honesty that broke the fourth wall within wrestling’s fictional world) have been subtly edited to remove some of the sting of reality that Vince himself probably regrets letting into his WWE Universe.

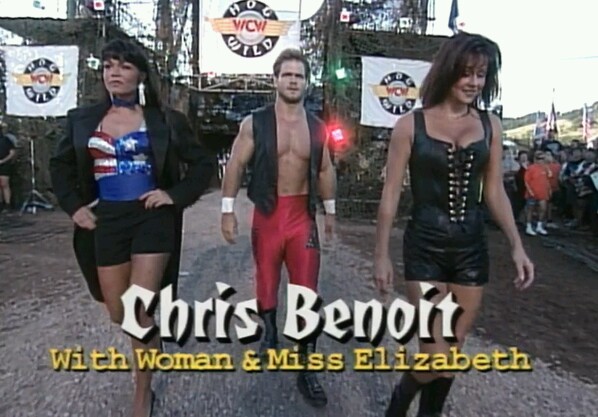

Black & white films get colorized, television shows sometimes come to DVD with different licensed music, and trade paperbacks often collect classic comics with art restoration, but none of those instances feel like someone trying to steer your memories. This sort of historical recreation is pointless, because no amount of editorializing will change what we as fans remember. You can’t watch Over The Limit ’99 without thinking about Owen Hart’s tragic death that happened in the middle of the event. You can’t watch ANYTHING involving Chris Benoit without thinking about him killing his wife, his son and himself. No carefully worded disclaimers can alter that.

Benoit, his wife, and Macho Man’s ex-wife. No one from this image is still alive. Screenshot courtesy of @SundownMotel,

The rose colored tint of nostalgia cuts both ways. For fans who just like to relieve their favorite moments from wrestling history, or just experience oddities like old Chef Boyardee commercials, The Network has existed for quite some time. They just called it “YouTube.” Momentarily revisiting key moments and turning points is fun and all, but it creates a false sense of how things really were. Imagine just watching the best scenes from Buffy The Vampire Slayer? Watching Angel become Angelus and “Fool For Love” you might feel differently about the series than you would if you had to sit through the entirety of Season Five. Likewise, Grant Morrison’s run on New X-Men is a lot better if you ignore the Igor Kordey issues.

With The Network you can consume wrestling stories the way they were originally conceived, in the context of being segmented over months of weekly shows. Nostalgia hounds remember the Attitude Era by its high points, many of them involving Steve Austin battling authority figures as a much beloved antihero, but looking up those matches on YouTube makes you forget some of the weaker stories happening on the mid card. In wrestling, a character arc might take a lot longer to work, based on the nature of the business. Austin’s ascendance to the top as one of wrestling’s hottest acts of all time really starts in summer of 1996 and isn’t fully realized until spring of 1998. If you’ve got tons of free time to kill (and The Network exists to kill free time) you can relive that build in full, and feel the length of breadth of his character’s struggle.

The WWE has always been great at mythologizing. Wrestling is the art of taking two people, one good, one bad, and building them up separately until such a time that you can make lots of money promoting them finally fighting. It works well in boxing and UFC, albeit with less scripted results, but McMahon’s company as always been ace at building up a feud or a moment to feel truly special. Hulk Hogan body slamming Andre The Giant at Wrestlemania III is the stuff of legend. It’s the kind of moment I can only picture in the context of a beautifully edited WWE montage, an art form unto itself. Rewatching WMIII the regular way, that match just did nothing for me. I intellectually understand it’s importance, but the match just didn’t move me. The danger in making something up to be an Olympian moment, slowly growing a shade of untouchable moss with every passing year, is that finally watching it in its original form can be reductive.

The Network makes it possible for some truly unsung arcs in professional wrestling to be consumed the way they deserve to be consumed, but the cost is that it brings Godly high points down to a human level. Maybe instead of a democracy, there’s something strangely socialist at it’s heart.

Excuse me. I have to go wash off this communism with a little Sgt. Slaughter.

Watch out, Sarge!