We at Deadshirt like to fancy ourselves pretty dedicated to popular culture with a combined knowledge of all things media that borders on the encyclopedic, but no one is perfect. There’s just too much music, too many films, too many comics, and way too many television episodes out there. No longer will we have to harbor the secret shame of not having experienced an expected work. Here is where we fill in the missing gaps.

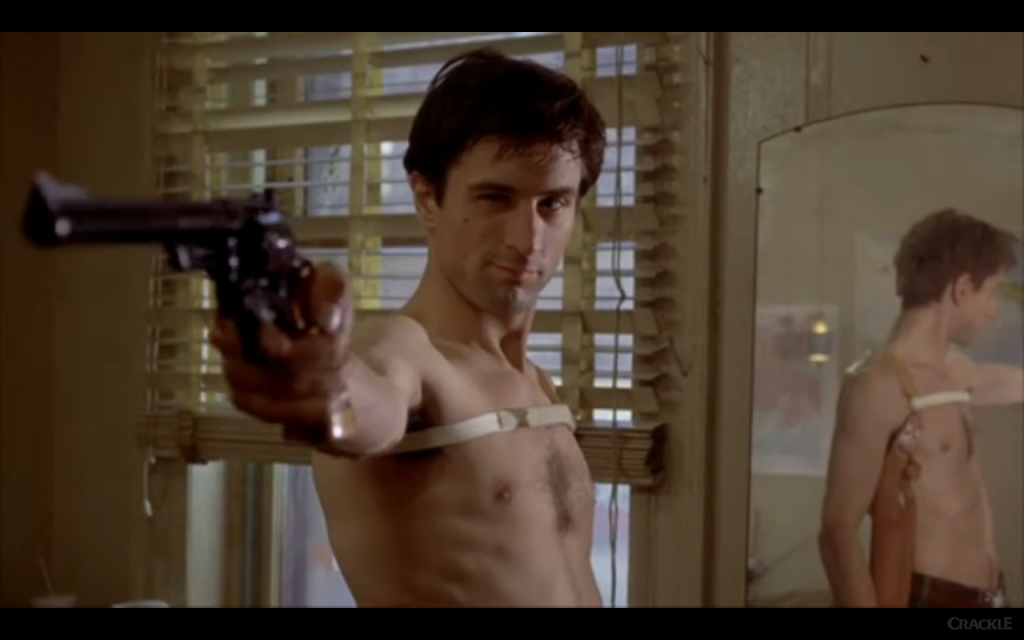

Robert DeNiro as Travis Bickle. (Source: A Flick A Week)

When we were asked to come up with gaps in our pop culture knowledge to mine for this feature, I wracked my brain quite a bit. I’ve actually been putting some effort into filling mine in of late, for its own sake and just to understand more of the influences that steer our lives. But I kept circling back to Scorsese—a generally yawning chasm in my credentials as a film geek, though I’ve recently seen Hugo and GoodFellas—and realized that I’ve yet to see a movie that I’ve probably joked about a dozen times, a movie that made the careers of several actors, a movie that pretty much inspired a wacko to take a shot at the president of the United States of America. Nope, I’ve never seen Taxi Driver.

Until now.

Holy crap, this movie came out in–checks–1976? It feels shockingly modern, which just speaks to how very influential it was. The camera work and the color palette have that timeless quality, much like the various Godfathers. The story feels timeless too, despite the fact that it is clearly rooted in the politics of the time.

But the more things change, the more they stay the same. New York isn’t the pit of decay that torments Bickle (and I now realize, his spiritual son, Watchmen’s Rorschach) anymore. But there are parts of the US now that are even more haunting. Idealistic politicians being targeted by the very people they seek to help? That’s an old familiar story in this day and age, isn’t it?

One of my favorite parts of this movie is how it refuses to “tell.” It “shows” us plenty, often climbing into Travis’ own head and forcing us to share his POV, but it doesn’t hold our hands. We don’t see Travis run out and buy a bunch of Palatine posters as his obsession develops—or god forbid, sticking up a bunch of strings and thumbtacks and newspaper articles like every other psycho in Hollywood does—they just appear, as Travis takes to waving his gun and brooding. Even his voiceover skirts around some of what he’s really thinking, as our own thoughts often do when we can’t confront ourselves. The words “racism” and “assassination” and “pedophilia,” the words “insanity” and “violence” and “sexism” are never uttered, but the movie is nonetheless about them, is dripping in these concepts.

In Travis we see a prototypical version of the 19-year-old MRA that so many of us have unfortunately encountered in our Twittering and Redditing and so forth. He has some marginally more legitimate reasons for being rough around the edges, since he’s poor, disconnected from his family, and a Marine veteran from Vietnam. But the similarity is there, having a faux-intellectual bent and a conviction that the world owes him something that he’s not getting, though even his internal monologue cannot articulate what, or why.

His problems at first seem to stem from PTSD, which has led to persistent insomnia. Oddly, while this is the first plot point presented in the film, it is never resolved, as we never see Travis sleep, and he has a superhuman ability to ignore what ought to be some crippling impairment as the months wind on. We also never find out what experiences have led him to the point where he is now. Was he on the front lines? Was he rear-echelon, jealous of the “heroes” who he saw in passing? Does it matter? The story would likely play out the same whether he was Captain Willard or Radar O’Reilly, but your feeling on this does impact how you interpret his joyous gun-handling later in the film.

Travis’ other problem is that he can’t stand the neighborhood. Part of that is that he’s racist—massively so. He’s no ‘60s Jim Crow racist, he’s the modern, 1970s-present day racist, who can always couch his feelings another way and still brag about how tolerant he is. He inarticulately rants against “the scum” of the streets but Senator Palantine (and a savvy audience) understands what he’s really talking about. This is one of the tools that Scorsese uses to tell us that, while Travis is the protagonist, he’s no hero. (Another, less subtle touch is the OMINOUS MUSICAL CUE that recurs when Travis is bein’ scary.)

DeNiro with Betsy (Cybil Shepherd.) (Source: Dr. StrangeCinema)

He’s sexist too, because he represents the worst of American male id. He stalks a woman who he holds up as an ideal among the “filth,” then when he’s caught he swaggers up to her with disarming self-deprecating smarm. Possibly the least realistic contrivance in the script is that Betsy does go with him, but this sets up the tragedy of his uncouth taste driving her away when even his jealousy and presumption did not.

Structurally, Betsy’s rejection is the film’s inciting incident. Wannabe Alpha Male Travis can’t express his sexual urges the “right” way, because he fails to attract Betsy or the porn-theater attendant. He can’t express them the “wrong” way, because Betsy’s revulsion reinforces his own self-loathing that he lowers himself to watching dirty movies (this being the one artifact of the plot that really centers the film in the pre-Internet age). So he represses his sexuality entirely and embraces violence instead.

We never hear Travis’ reasoning for wanting to take a shot at Palantine, but we understand it anyways. I hope I’m not being presumptuous when I suggest that a shared experience of many men is fantasizing about a way to seize the attention of someone who’s rejected them. The ultimate way to seize Betsy’s attention is to destroy her idol. And as a bonus feature, he martyrs himself in worldwide notoriety. It’s clear that Travis doesn’t even have a vague conception of Palatine’s populist and apparently laudable politics. All that matters is the fantasy that his insomnia-addled brain can’t distinguish from reality. Though from the point of view of Travis’ ex-Marine manly manosity, Palantine’s liberal politics probably aren’t exactly helping him either.

Derailed from this plot by his own hopeless incompetence (don’t make friends with Secret Service agents when you’re planning a hit), Travis becomes consumed by the third-act twist—Jodie Foster’s famous Iris. Of course, she ultimately embodies both “right” and “wrong” sexuality, and Travis again resolves the paradox with violence. What Travis doesn’t quite see is that his “date” with her is little less perverted than when he was masquerading as her john, because she’s a fucking preteen. But he doesn’t need to be introspective because self-destruction is his plan for everything.

Billie Perkins, Jodie Foster and DeNiro. (Source: Creative Cow)

I was surprised watching the movie by both the small size of Foster’s part—though it’s easy to see how she contributed so much to the film’s notoriety—and by the spent firework of Travis’ assassination “attempt.” His failure defies anti-climax. I thought for sure just going by Hollywood convention that he would be killed, or else escape successful. His failure does feel realistic, but it also emphasizes that Palantine wasn’t really what was important to Travis, or to the audience. As soon as he took serious notice of Iris, she became his obsession because she so perfectly embodies the corruption of beauty by the slums.

The end of the film was also incredibly unexpected to me. I can see a lot of different ways to interpret it. Does karma ignore intentions, only actions? Was Travis right to take the actions that he did after all? Was Iris delivered from Hell, or to Hell?

The way that I choose to interpret it is that life does not follow dramatic arcs, no matter how much deluded slobs like Travis or you and I think it does. Travis is a violent, dangerous man, killing people without warning or remorse. Scorsese emphasizes Travis’ victims’ pain, suffering, even their twisted courage in a way that forces you to acknowledge them, however monstrous, as human. Travis wanted nothing more than to go on a violent rampage and die dramatically. Instead, he woke up a hero. All thanks to the lens that Iris’ grateful parents perceived his actions through. On the surface, Travis seems to have inherited a wholly unjust reward. His girlfriend is back. He still has his job, and his friends. The newspapers and Iris’ parents love him.

But Travis didn’t actually get what he wanted. His torment refuses to end. He’s still working nights, indicating that he still has insomnia. He’s picked up a fresh batch of traumatic memories. Despite what he says to Betsy, his wound is likely still very serious. And the neighborhood hasn’t gotten any better, defying his fantasy that his own martyrdom could make a difference in the world. We can’t even take solace in Iris’ liberation, as she is returned to the parents she fled from in the first place and is suspiciously denied a voice in their final letter. In all likelihood Travis is still a ticking time bomb, just on a delayed fuse for awhile. When he blows, Betsy will be nearby. And the last statement from the filmmakers on the matter is the return of the ominous musical chord, at the very end of the hallucinogenic credits sequence. Travis Bickel lives on, though he may not deserve it, and the tragedies he will inflict on himself and others have not ended.

And there is the popular theory that Travis died in the raid, there would be no way that his imagined with only one foot in the door happy ending could actually happen.