“Could you kill your best friend?” reads the Battle Royale theatrical poster, summarizing the psychological horror story in one burning question.

First published in 1999, Koushun Takami’s novel Battle Royale took place in a Japan under totalitarian rule, where its youngest citizens are subjected to the deadly “Program.” Every year, a class of ninth graders are abducted and sent to a deserted island where, outfitted with weapons, they must kill all of their classmates over a period of three days, until only one student survives. Some students gleefully join in the game, some are merely victims caught in the crossfire, and some hold onto the desperate hope of escape.

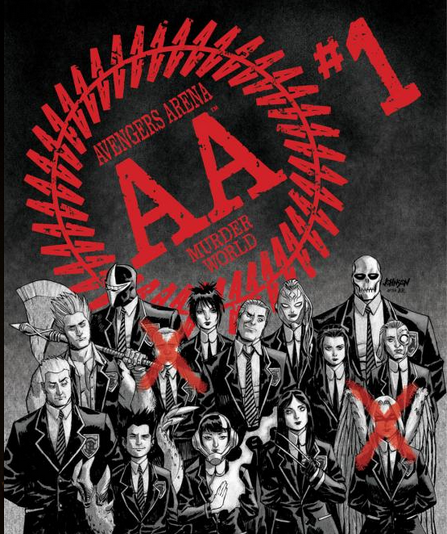

15 years later, Battle Royale has lost none of its capacity to shock readers, and its influence is felt not only in film and fiction, but comic books as well. The 2012 Marvel comic Avengers Arena copped the “kids kill each other on an island till only one’s left” premise from Battle Royale (and The Hunger Games), and also—somewhat shamelessly–its poster and logo design. In the early 2000s, Takami scripted an official Battle Royale manga with art by Masayuki Taguchi, which exaggerated the book’s violence and sexual content to a grotesque, even absurd degree. Tokyopop licensed the series, but Takami’s script was extensively re-written in English by Keith Giffen, who awkwardly inserted a brand new “reality show” aspect to the plot in an attempt to be a crossover hit with American readers.

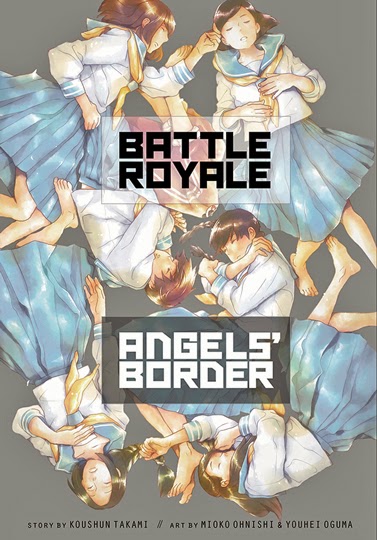

Koushun Takami returns to his island of doomed teenagers once more in Battle Royale: Angels’ Border, a single-volume manga with a significantly different approach than the previous series. Rather than adapting the entire novel, Angels’ Border focuses on a small group of characters in two stories that function as missing chapters. Late in the original novel, protagonist Shuya Nanahara is rescued by a group of six girls, led by class rep Yukie Utsumi, who have boarded themselves in a lighthouse. The girls are a tightly-knit group of friends and none of them want to participate in the Program, but Shuya’s unexpected arrival sows seeds of fear, and well, like the rules say: there can be only one survivor.

The lighthouse sequence is one of the most memorable and tragic in the novel, and it’s understandable why Takami would want to spotlight these girls in particular. Episode One, illustrated by Mioko Ohnishi, is narrated by Girl #12, Haruka Tanizawa. Before the Program, Haruka was a normal, athletic junior high school girl, but she considers herself abnormal for one reason: she’s in love with her best friend, Yuki Utsumi. Haruka knows her love is unrequited—Yukie has her own crush on Shuya—but she wants to stay by Yukie’s side for as long as she can.

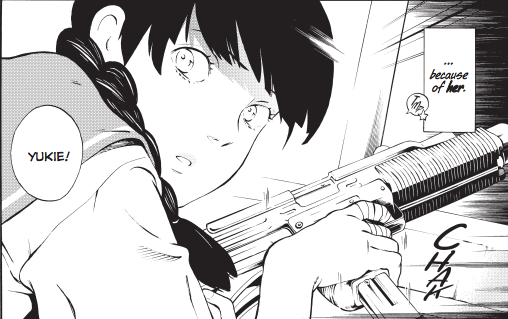

Under Ohnishi’s pencils, Haruka and Yuki could be the cute, lovable protagonists of any shoujo manga, which makes it all the more horrifying when violence breaks out. Shuya appears only in a few panels, but is handsome enough that it’s instantly understandable why he’s the class heartthrob. And Mitsuko Souma, the deadliest girl in class, is perfectly crazy-eyed in her cameo. The art is a complete contrast to Masayuki Taguchi’s (the girls look like average teenage girls rather than overdeveloped sexpots), and never feels crass or exploitative.

Episode Two stars Girl #19, Chisato Matsui, and is told partly in flashbacks as she remembers a chance—but fateful—meeting with class bad boy Shinji Mimura. The two teenagers have a long talk about faith, family, and their oppressive government, and though they have very different outlooks, they still dare to “leap” for their future. Youhei Oguma’s art favors dark, scratchy lines, in keeping with the story’s ominous tone. It opens with the images of a crow and a schoolgirl’s corpse dashed upon the rocks, a sharp contrast to its joyful, exuberant final page (perhaps in the end, there’s more than one way to “win” this game).

Takami’s talent for characterization shines in Angels’ Border. One of the novel’s greatest strengths is that it fleshes out nearly all of the 42 students trapped in the Program, giving them distinct personalities, goals, and backstories that prevent them from being mere cannon fodder. Haruka and Chisato were two of the least defined characters, so their stories feel new and relevant rather than a retread of material already depicted in the book. They feel like real, authentic teenage girls; they’re not skilled huntresses or quippy vampire slayers, but they dare to hope in a hopeless situation, and are no less strong for it.

Battle Royale: Angels’ Border is released as part of Viz Media’s Signature line of manga, and extras include a color plate of the lighthouse, an afterword by Takami, as well as Takami’s original scripts to the artists. I’ve never seen an original script included within a manga before, and a tiny devil on my shoulder wonders if this is a sly dig at Tokyopop’s distorted, inaccurate adaptation of the previous Battle Royale manga. Okay, probably not, but it’s fascinating nevertheless to see how the novelist Takami approaches writing a manga based on his characters.

The two stories in Battle Royale: Angels’ Border rush to their bloody conclusions, but the act titles, simply named “Hope,” “Yearn,” and “Fly,” among others, hint at the greater depth within. Amidst the horror, Battle Royale is about the hope and optimism of youth.

On the Battle Royale syllabus I’d rank Angels’ Border as advanced reading, rather than for beginners. A few pages are spent setting up the premise—evil government, kidnapped kids, lots of guns, one survivor—but it assumes the reader is already familiar with the larger story and cast surrounding the lighthouse. If you’ve never read the novel or seen the film, I’d recommend starting with those instead. (I was never a fan of Takami and Taguchi’s manga.) Angels’ Border is a strong, satisfying read, but it’s not the full story.

Battle Royale: Angels’ Border is available now in stores.