Star Trek is an enormous and complex cultural entity whose impact on politics, technology, and storytelling are undeniable. It’s also a flawed and problematic as any other massive media franchise. Lifelong Trekkie and Deadshirt Editor-in-Chief Dylan Roth attempts to make sense of it all for die-hards and outsiders alike in his bi-weekly column: Infinite Diversity.

“You will always be a child of two worlds. I am grateful for this, and for you.”

– Vulcan Ambassador Sarek, to his half-human son Spock. (Star Trek [2009])

Star Trek presents a future humanity that’s united, no longer recognizing racial or ethnic divides and just identifying as “human,” though with significant and downright unacceptable cultural losses. However, that post-racial attitude only extends as far as other human beings. When it comes to diversity in space, Star Trek is on the opposite extreme. There are thousands of alien races out there in the galaxy, and among the community of worlds, race is an obsession. In the world of Trek, your species is your primary identifier. Individuals are constantly pre-judged based on their race, be they Klingon, Vulcan, Ferengi, etc. The expectations for your personality or even your expertise are set immediately, and because of the nature of alien cultures on Trek, those expectations are usually met. Humans are likewise profiled when they encounter aliens, but while aliens get stereotypes like “conniving” (Romulans) or “paranoid” (Andorians), humans get super flattering ones like “curious” and “inventive,” because we’re the ones writing the show. With its alien characters, Trek often reinforces the idea that you are where you come from, and who you come from, and that’s not a very popular idea, at least in the 21st Century.

Where this gets more complicated is through the examination of Trek‘s multitude of characters who belong to more than one species, either by birth or circumstance. While no one in Trek would bat an eye at a human character with what today would be considered to be a mixed racial heritage, when a character is born of more than one species, it tends to define their lives. Every Trek series features at least one character who must choose between two tribes, two destinies suggested by their race, and each of these characters deals with this conflict in a unique way.

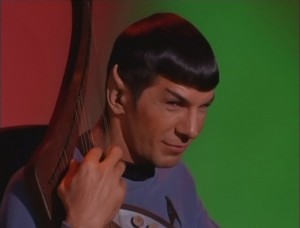

“I am a Vulcan, I have no ego to bruise.”

Spock is the son of Sarek, the Vulcan Ambassador to Earth, and Amanda Grayson, a human teacher. Born and raised on Vulcan, Spock fully embraces the Vulcan way of life, dedicating himself to logic and control over emotion. He follows what’s considered a very Vulcan career path, that of a scientist. His mother, too, lives in Vulcan fashion, measuring but not totally hiding her emotions, and takes no offense to Spock’s rejection of “human” emotion, though she’s often the one to remind Spock that it’s okay, even necessary, to let yourself feel now and then. Teased in his youth for not being fully Vulcan, Spock is relentless in his pursuit of Vulcan perfection, even nearly mastering the Vulcan discipline of Kohlinar, which is the complete purging of all emotion.

It’s important to note that Vulcans are not naturally emotionless, and in fact may have an even greater predisposition toward emotional behavior than humans. While it’s occasionally suggested that Vulcans have a neurological advantage when it comes to suppressing emotion, their dedication to logic over emotion is predominantly a cultural phenomenon, not a biological trait. Because humans as a whole do not value the same level of emotional control as Vulcans, it’s easy for emotionalism to become humanity’s defining trait from a Vulcan perspective, whether or not that’s fair. To young Spock, growing up half-human among Vulcans, emotionalism equals humanity, logic equals Vulcanism.

Spock’s steadfast pursuit of logic is likely motivated by the need to prove to others, and to himself, that he’s really a Vulcan. His Kohlinar training could be seen as seeking to symbolically purge his human half altogether, and finally feel like he belongs among his own people. If he can be the platonic ideal of a Vulcan, no one will question his nature again. This is all subtext–Spock never brings up being prejudged by other Vulcans (at least not in the Prime Universe), it is always brought up by others, usually his human mother.

The fact that Spock identifies only as a Vulcan is more interesting when you consider that Spock spends much of his adult life (over a century) among humans. As a member the almost entirely human crew of the USS Enterprise, Spock is even more an “other” than he was on Vulcan, but here he leans hard into it. Rather than using this opportunity to be both “sides” of itself (if you buy the idea that simply having human DNA really influences his behavior in any way), he plants his feet in Vulcan identity, carrying it with a sense of pride and superiority. He never hides his human heritage, but when asked what his species is, he answers “Vulcan,” only adding that he’s half human if it’s specifically relevant. While he’s surrounded by the part of his heritage with which he doesn’t identify, he’s more comfortable aboard the Enterprise, where he’s the most “Vulcan” person around. It’s telling that when his time with Starfleet is over, Spock relocates to Romulus to once again serve as an ambassador, an authority on Vulcan-kind among non-Vulcans.

“I am Klingon. If you doubt it, a demonstration can be arranged.”

Like Spock, The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine‘s Worf is one of the franchise’s most iconic characters, and gets what might be the most long-term growth and development of any Trek character. Born to a politically powerful Klingon house, Worf’s family is killed in an attack by the Romulans when he is just a boy. He is rescued by a human Starfleet enlisted man, Sergey Rozhenko. After being (falsely) informed that Worf has no surviving family, Rozhenko brings Worf home to a Federation colony, where he and his wife Helena raise him in an environment made up of mostly humans and no other Klingons.

Sergey and Helena do their best to make sure Worf is able to hang onto his Klingon culture, but having little access to other Klingons (Federation-Klingon relations have never been incredibly chummy, even during peacetime), Worf constructs his own idea of what it means to be Klingon, using himself as a model. If you were to ask Worf what qualities are essential in a Klingon man, he would say he should be stern, forthright, emotionally guarded, spiritually disciplined, and above all, truthful. Worf enjoys his solitude, so when confronted about his standoffish nature, Worf hides behind the idea that Klingons don’t socialize. Worf doesn’t have much of a sense of humor, and almost never laughs, so he tells himself that humor isn’t Klingon. Worf never lies, and knows from his sacred texts that honor is valued above all else, so honesty is a trait he should expect all Klingons to share. And why not? There’s no one around to serve as a counter-example.

It’s not until we see Worf interact with other Klingons, Klingons who have spent their whole lives among their own kind and culture, that Worf’s cultural assumptions are revealed as baseless. Like Spock, Worf has worked long and hard to become an ideal personification of his race, but whenever he meets other “real” Klingons, they fail to measure up to his own example. Klingons (in general, but Star Trek loves these generalizations) are loud and boastful. There’s nothing a good Klingon enjoys more than spinning a tall tale to a crowd of friends around a roaring fire, exaggerating the details of their victory in battle and erupting into laughter. Worf couldn’t fit in worse, and they make sure he feels it at every opportunity. Worf’s individual personality and his Klingon rituals are both totally respected aboard the Enterprise, but among Klingons he is ridiculed, insulted, and condescended to. He has to prove himself constantly, and it usually takes an extraordinary act of honor or bravery to win over their respect.

When the Federation refuses to get involved in the Klingon Civil War, Worf resigns his Starfleet commission to fight for the more honorable side.

It’s likely that Worf’s disappointment in Klingons in general to meet his expectations is why Worf is so unafraid to challenge Klingon authority. When Worf becomes embroiled in high Klingon politics, he typically takes a stance of moral superiority, disgusted at their leaders’ dishonest maneuvering. Even as those who call themselves “real” Klingons challenge his ideal of what a Klingon should be, Worf holds fast to his values and even attempts to inject them back into Klingon culture, taking every opportunity to maneuver more worthy candidates into power. This man, orphaned and isolated from his own people, develops a child’s idealized version of what his lost culture would be like, and when he finds the reality lacking, he molds society to better suit his fantasy.

“I inherited the forehead and the bad attitude. That’s all.”

Spock and Worf are both characters who identify very strongly with the non-human parts of their backgrounds, despite living in a human-centric environment. But what happens when someone in Star Trek isn’t proud of what makes her different?

Voyager‘s B’Elanna Torres is sort of a sad mirror image of Spock’s story. B’Elanna is the daughter of a Klingon mother, Miral, and a human father, John Torres, whose relationship falls apart when she’s still a child. Like Worf, she grows up in an environment with no other Klingons, with the exception of her mother, who B’Elanna recalls as overbearing, hot-tempered, and obsessed with Klingon ritual and spirituality. Like Spock, she never feels like she fits in on her childhood homeworld, which is populated mostly by humans, and she’s openly teased or mocked by other kids for being part alien on at least two occasions.

Young B’Elanna overhears her father making a racially-charged remark about Klingons shortly before he leaves the family. She never gets over it.

Some time before B’Elanna’s teens, her father John abandons the family, saying that he can’t handle the stress of living with two hot-blooded Klingon women. B’Elanna, who’s already annoyed by her mother’s adherence to Klingon culture, develops a deep resentment for all things Klingon, blames her father’s departure on Miral’s Klingon temper and fixation on honor and the afterlife. B’Elanna also learns to hate the Klingon side of herself, the part that she feels keeps her from connecting with people.

B’Elanna is not shy about her feelings toward Klingon culture and her own Klingon heritage: she doesn’t like it, she’s not interested, she doesn’t want to talk about it. Despite her mother being the more reliable parent in her life, B’Elanna still grew up among humans and identifies more closely as a human, always laying the blame for her shattered family on her mother, the one who made her different. B’Elanna’s relationship with her mother is not unlike a second-generation American immigrant who wishes her parent would stop talking about “the old country” and allow her to assimilate.

Spock may have quietly stepped away from his human side in favor of living as a Vulcan, but Torres openly does not want to be Klingon. When a Vidiian scientist splits her into two people, one fully human and one fully Vulcan (which is one of the most ridiculous premises for a Trek episode, cheaply personifying Torres’ inner struggle into the physical world), the human Torres dooesn’t want to be rejoined with her counterpart. Years later, when Torres is pregnant with a three-quarter human, one-quarter Klingon daughter, she becomes obsessed with finding a way to bury her Klingon traits so that her child will appear fully human. Her experience of being isolated and prejudged for having forehead ridges and a short fuse, which she believes is the cause of her father’s abandonment, makes Torres hateful not of the people who mistreated her but of her own “unusual” traits.

B’Elanna eventually puts her conflict with her mother aside, risking her own life to rescue Miral’s soul from Klingon Hell.

Stories about B’Elanna’s struggles with Klingon heritage often shine an unflattering light on Trek‘s portrayal of species/race identity. While B’Elanna couldn’t make it more clear that she doesn’t want anything to do with Klingon-ness, her shipmates aboard Voyager bring it up almost constantly, and their fixation is rarely framed as a negative. As much as Spock was “Vulcan guy” aboard the Enterprise, B’Elanna is the “ship’s Klingon” aboard Voyager. With Spock, the tension of “otherness” is usually avoided because Spock thinks being Vulcan is great and enjoys talking about it. In the case of B’Elanna, this makes for some very uncomfortable viewing. It’s the equivalent of a history teacher repeatedly asking a lone Iranian-American student to comment on the Middle East, while each and every time she answers “I was born in Newark.”

Lt. Torres just wants to be treated like everyone else, and the crew, her surrogate family, just will not let it go. They want her to accept her background and stop hating on her Klingon half, which is great, but what she wants is to stop feeling like an outsider, and the rules of Trek don’t really allow for that. In Trek, you are your species; you can never know who you are until you embrace where you come from, even if you think where you come from is stupid and horrible. (Imagine a character whose ancestor fought for the Nazis being frequently badgered by friends that she should take pride in the world-conquering, mass-murdering ambitions of her heritage, simply because “you should embrace your cultural past!” when what she really wants to do is just be herself instead of being defined by previous generations.)

Certainly, no one should have to feel ashamed or isolated because of their racial background, whether that race is based on what continent your ancestors are from or what star system. B’Elanna Torres’ self-hatred over being part Klingon is tragic and unhealthy, and her crew’s efforts to make her more comfortable with herself are well-intentioned. Certainly, intervening to stop B’Elanna from “white-washing” her unborn child is the right thing to do. But the degree to which one identifies with their ancestry must be up to the individual, B’Elanna can’t change how she was born, nor should she feel the need to do so, but she should get to choose how she wants to live. What kind of “perfect society” is she living in if she can’t be who she is?

Next time: We take a break from the heavy social justice fare for something a little lighter: FAN FILMS.

Infinite Diversity will return in two weeks! Follow @DeadshirtDotNet on Twitter to keep up with what’s new here on Deadshirt, and feel free to tweet @DylanRoth with suggestions for future topics for Infinite Diversity, or just to talk about Trek. He truly never gets tired of that.