Film is an entertainment medium that, by its very nature, tends to reward the viewer in rewatch. Sometimes movies even reveal to us how we’ve grown or changed since we last saw them. Our own Max Robinson reassesses old favorites, seasonal classics and the occasional oddball lost under the couch in his monthly column, Stale Popcorn.

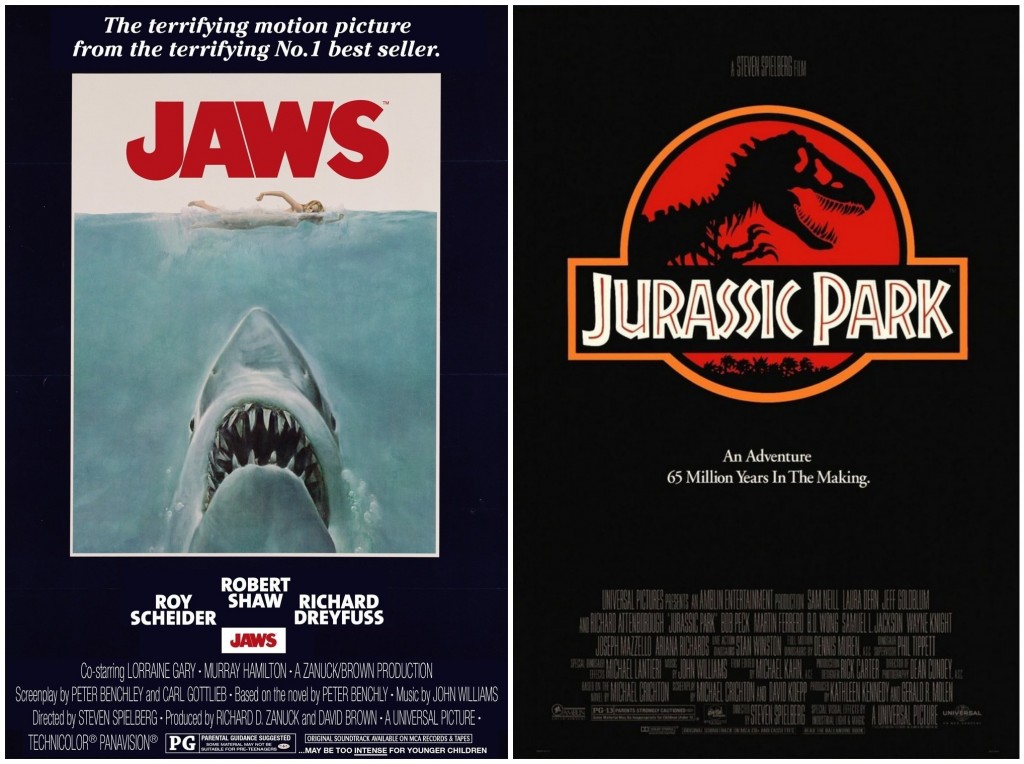

Jurassic World is out in theaters, the latest link in an evolutionary genre chain dating back to the Steven Spielberg’s original Jurassic Park and, almost certainly, Jaws. Man vs. animal movies aren’t anything new—flip the channel to SyFy on a given day—but Spielberg’s fascination with nature is really intriguing as a recurring theme in his resume. To that end, I think Jurassic Park and Jaws tread very similar territory.

On a purely visual level, it’s impossible to ignore Spielberg’s focus on the stark difference between human and animal, which he emphasizes through eyes. In Jaws, crazed shark hunter Quint describes shark eyes as black and doll-like. One of Jurassic Park‘s more iconic visuals is the dilating pupil of the T. Rex when it’s caught in the glare of a flashlight prior to one of the movie’s big action sequences. In the opening of the film, Spielberg deliberately cuts from dinosaur wrangler Muldoon’s wide, frightened eyes and the comparatively alien pupils of a captive velociraptor (Skip ahead to 3:00 to see what I mean).

All of this serves to remind the viewer that the monsters of these particular creature features aren’t traditional movie foes. They’re animals, not bad guys. They aren’t driven by malicious intent; they don’t operate on a level beyond what they need to do to survive. They’re predators, and our hapless heroes are McNuggets with legs who happen to be in their path. Muldoon and Quint, for all their machismo and experience, die at the hands of their respective quarry because they aren’t able to think like they do. How could they possibly?

A big sticking point in the philosophy running beneath both films is that events are set in motion by violations of the natural order. Jurassic Park‘s heresy is more obvious; InGen’s corporate scientists spit in the face of millions of years of natural selection to revive extinct flora and fauna with more thought for profit margins than the moral or ethical implications of playing God. Jaws‘ nameless menace, however, poses a broader question. Why is the film’s Great White so huge? Why is it constantly feeding? Beyond “well, duh, it’s a movie,” it’s also worth considering that the mere existence of “Bruce” doesn’t make any sense. That only adds to the film’s pervading sense of something being wrong. The Amity Island shark and Jurassic Park’s reptile inhabitants are mutants, explicitly so in the latter’s frog DNA-spliced creations. These abominations should not exist, but because they do, the civilized world of the film must suffer.

Also consider that the animal rampages in the films thrive thanks to the failure of authority figures, from the benign but arrogant John Hammond to the cowardly Mayor Vaughn. Their ignorance and refusal to listen to reason until it’s too late enable the breakdown in accepted order that results in human slaughter. Vaughn holds off on closing Amity Island’s beaches until three people are dead; Hammond obliviously brings his own grandchildren to a remote island filled with killing machines and is surprised when they’re put in harm’s way.

I think a big part of why Spielberg is so interested in the animal kingdom is that the portrayal of animal nature serves to emphasize and highlight the comparative complexity of human nature. Jeff Goldblum’s Ian Malcolm has an almost religious reverence for “chaos theory,” which in turn is responsible for his distinctly human decision to distract the T. Rex which has pinned down Lex and Tim Murphy’s Jeep (at great physical cost). Shortly thereafter, Alan Grant bonds with the Murphys over dumb jokes as they recover from the day’s ordeal. Spielberg casts this against the backdrop of grazing Brontosauruses to highlight the differences between these unusual families. Later on, Grant plays a prank on them by pretending to be shocked by an electric fence, turning around with a sly grin. The basic act of survival has placed Grant, Tim, and Lex in a place where they trust each other implicitly; there’s an unspoken intimacy here. Compare this to Jaws‘ own version of this scene, where Quint, Hooper, and Brody sing, drink and humorously compare their various scars. The men, who’ve spent most of the movie bickering, have found a way to relate to one another amidst their doomed mission at sea. Storytelling is a human characteristic, and that this is what the heroes of these films turn to in times of duress speaks volumes. What does John Hammond do when holed up in the park’s visitor center with Ellie Sattler? He confesses to her; he seeks forgiveness.

By the third acts of Jaws and Jurassic Park, it’s human cleverness born of necessity rather than physical prowess or major firepower that save the respective days. Brody, with Quint dead and Hooper nowhere to be found, barely survives because he’s able to wing an oxygen tank with a rifle shot. Sattler pushes past her instinctual terror to evade a pursuing Velociraptor and reactivate the park’s electricity, while teen hacker Lex’s computer skills are what bring the park’s security protocols back online. The Murphy children successfully hide from two raptors in an industrial kitchen that acts as a sort of hall of mirrors. Admittedly, Jurassic Park‘s leads are doomed until a Deus Ex Tyrannosaur lumbers into the destroyed visitor center and inadvertently buys them enough time to flee. Beyond being a cool visual flourish to end the adventure on, Spielberg makes this work as a resolution to the film’s insistence on the unpredictable nature of, well…nature.

Why do we love these movies? Because Spielberg has crafted enduring stories of human survival that emphasize the best aspects of human nature (selflessness, empathy, ingenuity) and hold our uniquely human failings against the pure instinct of animal behavior. We return to Jaws and Jurassic Park over and over again not just because of the spectacle of a CG T. rex or a surprisingly convincing animatronic Great White; we come back because we care about their human prey.

Enjoy Stale Popcorn? Contribute to Deadshirt’s Patreon funding effort!