It’s getting colder out there. It’s getting darker. In honor of “Noirvember,” Deadshirt’s decided to turn the spotlight on our favorite modern noir films of the last couple decades. Eyes forward, put the money in the bag and don’t get cute. This is Neo-Noirvember.

Neo-noir films keep characters on their toes because they know they can’t trust anyone, but in Christopher Nolan’s breakout film Memento, Leonard Shelby can’t even trust himself. Leonard’s predicament, a condition affecting his short-term memory, means he hasn’t been able to form new, lasting memories since the inciting trauma, a blow to the head from the mystery man who also raped and murdered his wife. Having only fragments of his past and no concept of the future, Leonard (Guy Pearce) lives forever in the present, driven only by the search for the “John G.” who took his whole world away.

This is a pretty straightforward premise, but the film’s initially confounding structure exacerbates things, placing the viewer in a disorienting approximation of Leonard’s POV. The film is split between two narrative through lines that eventually meet in a climactic middle. The present, shot with harsh, bright colors, unfolds in reverse, while a framing sequence set earlier in the time line unfolds chronologically, in documentary style black and white. The latter is designed to get across important exposition and offer an objective take on Leonard’s reality, where he himself calmly and naturally explains his dilemma, but it’s the backwards sequences that make Memento so special.

This half of the film is a series of intriguing serials with reverse cliffhangers, laid end to end in opposition to the forward moving flashbacks. The sequences are islands to themselves. When a scene begins, we don’t know where we’re coming from, and, even though we know from the last scene where we’re going, we don’t know how we’ll get there. Every new piece of information, however small, colors the previous scene a new shade. Tropes and figures in the noir tradition appear, but they shift from scene to scene. Joe Pantoliano’s Teddy fills no less than three central roles in Leonard’s life at any given time, whether friend or foe or acquaintance. Carrie-Ann Moss, as Natalie, might be a damsel in distress in one scene and a hideous femme fatale in the next.

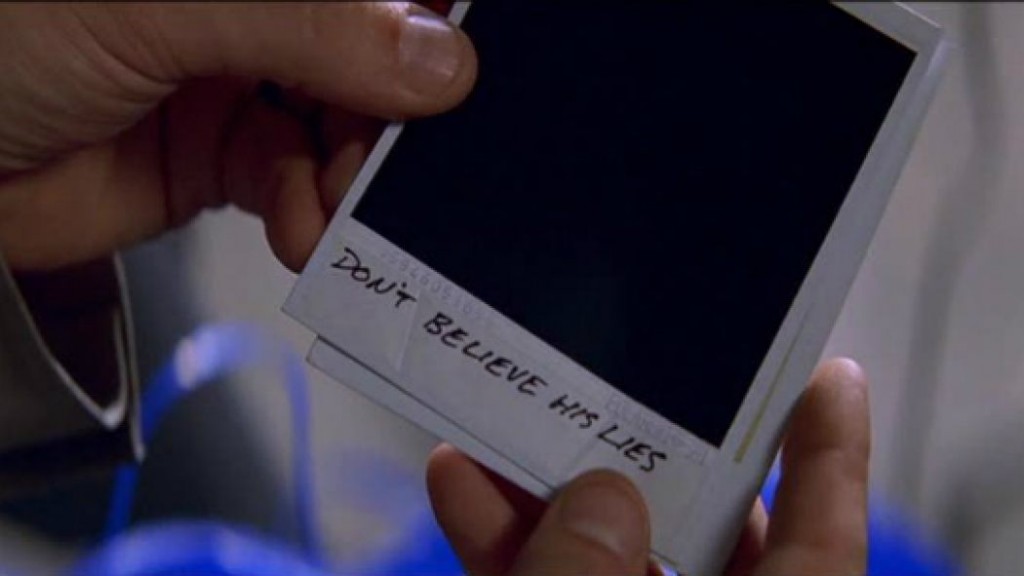

When events unfold in this manner, the difficulty of Leonard’s situation becomes readily apparent. He locks eyes with people he’s met on numerous occasions, but has to feign familiarity. He doesn’t know anyone’s intentions, and has to trust hand written notes, self drawn tattoos and Polaroids to maintain any semblance of trust in the world around him. In the absence of the subjective comfort of memories, Leonard is left with the dogmatic adherence to facts. Certainties are placed at a premium. The sound a door makes when you knock on it. The weight of a pen. The little things we take for granted every day are the brittle building blocks of Leonard’s world.

He has to have a system, so he doesn’t end up like Sammy Jankis, an accountant with a similar disorder Leonard met in his former life as an insurance investigator. Leonard uses the Ballad of Sammy as a mantra-like anecdote to express the complexity of his condition to those around him, but as details of his own life and Sammy’s blur, other aspects of what Leonard believes to be the truth begin to unravel. The facade he’s built around himself, like the faded ill-fitting suit he wears in the film, all call to mind the validity of his beliefs.

Everything audiences have come to love about Nolan’s work is all on display here, from the wry, efficient dialogue to the tightly wound story design. His films tend to open with smartly curated images that act as the entire film in miniature, from the blood stain that opens Insomnia to the sea of top hats from The Prestige. Here, the film opens with the story’s latest chronological moment playing out in reverse: a Polaroid fading slowly before being eaten back up by the camera that spat it out and a bullet retreating from the face of the photo’s subject. In this film, Polaroids, literal snapshots in time, replace memories, but devoid of context, they’re as unreliable as the subjective memories Leonard doesn’t trust. There’s a scene in which Natalie tries to crumple up one of his photos to get rid of it, and Leonard corrects her. “You have to burn them.” Why does he know that? How infallible can a system be when you designed it and you don’t even know who you were when you did it?

Everything about the film’s style, from the camera work to the neorealist tenor of the performances, is in service of curating a slightly skewed interpretation of reality. Pantoliano and Moss both make minor tweaks to their dispositions based on any given scene to highlight or downplay an aspect of their character. How much we like or dislike them tends to line up with how much Leonard trusts them. For his part, Pearce delivers an iconic update of the forlorn shamus archetype, with his gaunt frame and hollowed-out gaze. Unlike more stylized neo-noirs, Memento mines its primary drama and tension from the uncertainty of perception and the faulty nature of the human condition, rather than the theatricality of crime caper aesthetics.

The twists in Memento work so well because the film keeps you too busy guessing about the basic shape of the puzzle pieces to worry about the bigger picture: The dangerous lies we tell one another and ourselves and the damaging results.

Though crime fiction maintains a cynical, darkly hewed reflection of reality, the detective drama possesses an undercurrent of comfort. No matter how winding a road the quest for answers rolls down, there are always answers to be had, but in Memento, the very concept of truth and opacity have been shattered to such a degree that no reassurance can be found. It’s no surprise, then, that Leonard makes the choices he does, as the alternative, the truer option, is no option at all.

Check back each week for more Neo-Noirvember essays from Deadshirt.