With the release of the first X-Men film in 2000, audiences not only witnessed the dawn of the modern day superhero film boom, but also the beginning of a complicated franchise that would span sixteen years and nine films. With X-Men: Apocalypse on the horizon, Kayleigh Hearn and a rotating cast of merry mutants are revisiting the X-Men films from the very beginning, and examining the comic book storylines that inspired them. What would you prefer, yellow spandex?

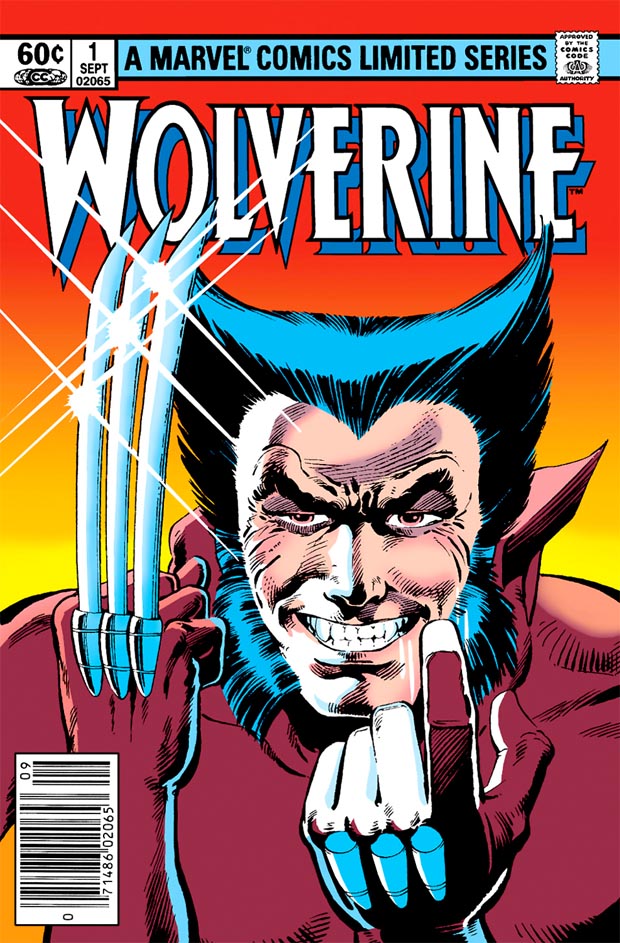

Wolverine #1-4 (1982)

By Chris Claremont and Frank Miller

Kayleigh: Chris Claremont and Frank Miller’s Wolverine miniseries was a major turning point for the X-Men franchise as it was the first comic to star Wolverine as a solo hero. If you’re an X-Men fan who resents Wolverine’s shift from the lone wolf of the team to the overwhelming star of the franchise, well, you can probably blame this mini for that. I only read this miniseries for the first time within the last year, and I’d say it generally lives up to its reputation as one of the best (or perhaps, purest) Wolverine stories ever told. The story of Wolverine journeying to Tokyo to rescue his lover Mariko Yashida, the miniseries showcases Chris Claremont’s versatility as a writer in what was an atypical X-Men story for the time. This miniseries is also Frank Miller’s only major contribution to the X-Men universe, but it left a crater-sized impact.

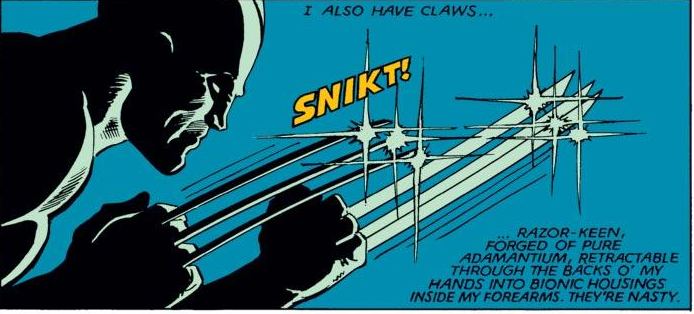

Max: This comic is an Arnold Palmer mixing Frank Miller’s love of ninjas, Claremont’s love of purple prose narration and their shared obsession with Tough Action Women (TM). There’s a ton of great stuff here but it’s interesting re-reading this at a point where (Miller especially) these writers’ usual ticks have defined their careers so much. I’ll be honest, I’m at the point with Claremont’s writing where my eyes glaze over when I get to the caption boxes, but this opening sequence of Wolverine hunting down a bear is great.

Kayleigh: Funny that you mention your eyes glazing over at Claremont’s narration, since I think this is one of the least overwritten (making it, I guess, just “written”) of Claremont’s classic X-Men comics. I’m on record liking Claremont’s purple prose, though at times his authorial voice can overwhelm the art. Here, he gives Miller’s art a lot of room to breathe. There are classic Claremontisms in the text (“I’m the best there is at what I do…” “No quarter asked, none given.”) but it absolutely feels like a Frank Miller comic.

Max: Absolutely. According to comics legend, this comic was the result of Miller and Claremont’s road trip home after a convention appearance. It’s pretty easy to see this as a few ideas Miller had rolling around and his head he managed to sell Claremont on.

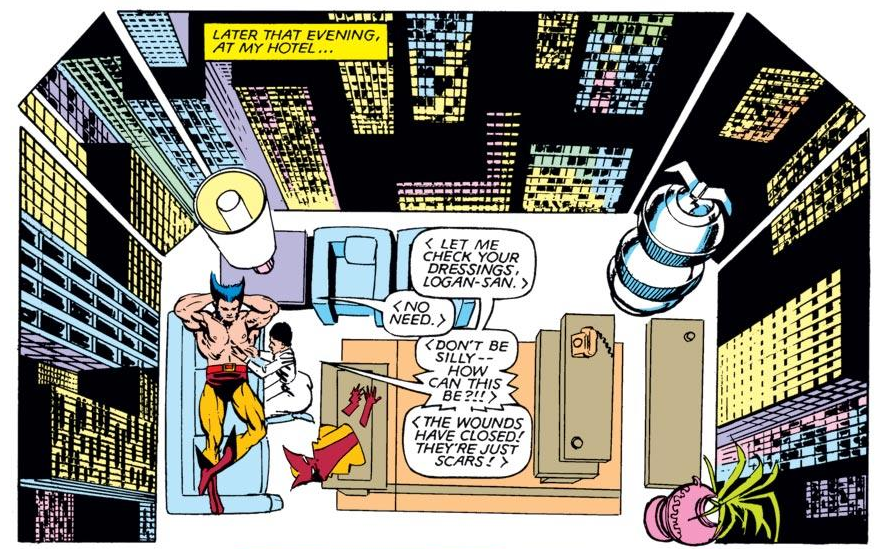

The Wolverine leans heavily on this comic so it’s funny going back to the source material and realizing it’s a comic where Wolverine goes to rescue his (previously seen in Uncanny X-Men) Japanese girlfriend then spends the next three issues drunk in a gutter after losing a fake sword fight with her dad.

Kayleigh: I can only approach this miniseries from my perspective as a white American woman, but Mariko’s portrayal here doesn’t hold up well. In both the comic and The Wolverine, Mariko is basically regulated to the role of the princess in the tower (Wolverine even calls her “princess”) who needs to be rescued, which gets even murkier combined with the miniseries’ rather exoticized version of Japan. Not that Mariko needs to be a warrior like Yukio, but Tao Okamoto’s Mariko feels more three-dimensional as a character. I think Miller and Claremont were coming from a place of admiration for Japanese culture, but the whole angle of Mariko needing to be saved from her abusive family by her white boyfriend (Logan’s friend Asano says he is “more truly Japanese than any westerner I have ever known,” like really) is awkward at best. This gets even more uncomfortable with the introduction of Yukio, who is verrrrrry much a Frank Miller female character.

Max: Wolverine as the viewpoint character into Japan in The Wolverine worked a lot better than it does here, mainly because there he’s a dummy who doesn’t know anything instead of this white samurai wish fulfillment figure for a male readership. Yukio is pretty much just Gail from Sin City except Japanese, the stuff with her being in love with Logan while still being obligated to obey Mariko’s evil father really drags all this down.

Kayleigh: The love triangle drags the book down in that it pits Mariko and Yukio against each other and leans heavily on the virgin/whore dichotomy. There’s a scene where Yukio is literally on her knees begging for Wolverine to love her, and it’s so distastefully atypical of the usual dignity Claremont gives his female characters. It’s possibly too convenient to put this all on Miller, but when Yukio next appears in Uncanny X-Men, sweeping Storm off her feet and giving her a punk makeover, she’s a much more fun character, partly because she’s no longer pining for Wolverine. The Wolverine was smart to drop these weird gender dynamics by making Mariko and Yukio women who actually care about each other, not romantic rivals.

Max: There’s a lot of weirdness here that hasn’t aged well but this is also from the era of Peak Frank Miller so we do get some really great sequences of Wolverine fighting The Hand, fresh off their appearance in Miller’s Daredevil. There’s a nighttime rooftop chase where Yukio and Wolverine are fighting ninjas against a backdrop of huge neon signs and billboards, it’s gorgeous. This is the best 80s Marvel gets, right there.

Kayleigh: Frank Miller’s increasingly stylized art is so controversial today that it’s like a gut-punch reading his classic material, because it’s so good. Miller’s use of negative space in his layouts, particularly during action sequences, gives his art an intense clarity of purpose. I have this mini collected in an omnibus along with the John & Sal Buscema Magik miniseries from around the same time period, and it’s interesting to contrast Miller’s stylized, manga-influenced art with comic pages that are more traditionally dense and panel-packed. There are action sequences in this miniseries completely devoid of sound effects or background images, but you don’t need them because the figures are so crisply drawn.

Max: There isn’t really a whole lot to sink your teeth into here, story-wise? It’s really comes down to Wolverine fighting Lord Shingen, and while their two duels are really beautifully drawn, there’s no real conflict here beyond Shingen not liking westerners and being evil.

Kayleigh: In The Wolverine, Logan’s internal struggle is whether or not he wants to give up his immortality and live (and die) like a normal man. In the comic, Wolverine is more torn between his human and animal natures, which is about as classically Wolverine as you can get. The end of the story hinges on Wolverine proving himself worthy of Mariko’s love, which is pretty admirable, and gives the Logan/Mariko romance a bit more dimension and believability than the “beauty and the beast” style romance it was when Claremont and John Byrne first introduced the pairing.

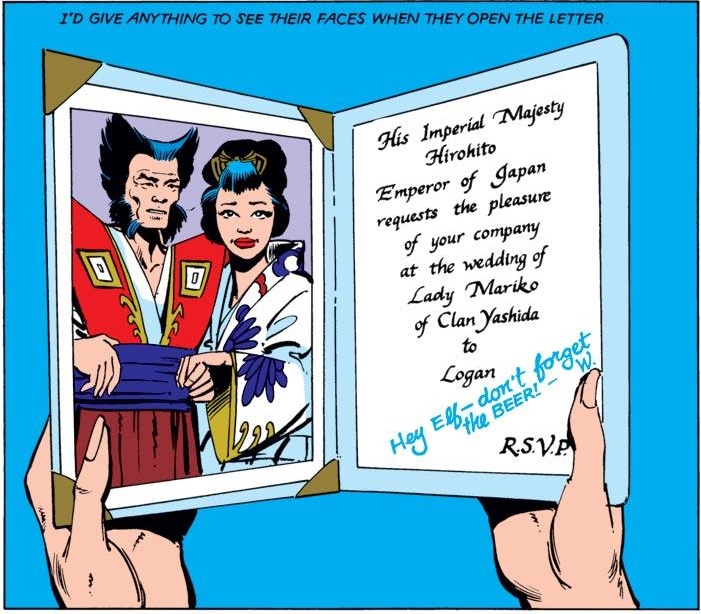

Max: The X-Men themselves only have a one panel cameo here and it’s when Wolverine sends out the (hilarious) invites to his wedding.

Kayleigh: The X-Men appearing for one panel on the very last page of this miniseries feels really daring for its time, too. Claremont’s ability to weave his characters through different genres is really underrated—at their peak, the X-Men could fit seamlessly into space operas, vampire stories, and international crime dramas. This is a Wolverine comic without supervillains or any other mutants, but it’s still the ultimate Wolverine story.

Next Week: Time keeps on slippin, slippin’ with Days of Future Past!