For some people, watching a movie set in or around Hollywood is just too much inside baseball. But for the diehards, exploring the world of filmmaking has birthed some of the medium’s greatest triumphs. Over the next few months, our very own Dominic Griffin is going to revisit the gems of Movies on Movies…

The cultural divide at the heart of David Mamet’s setup State and Main speaks to why films set in and around the world of moviemaking will always exist at a distance from the general viewing public. As the film begins, director Walt Price (William H. Macy) and a skeleton crew descend upon the small town of Waterford, Vermont. Walt has just been driven out of an expensive location in New Hampshire and that town is holding the old mill set they built for ransom. Waterford, however, has its own actual old mill. With shooting set to start in a few days, it’s the perfect place to stage their production.

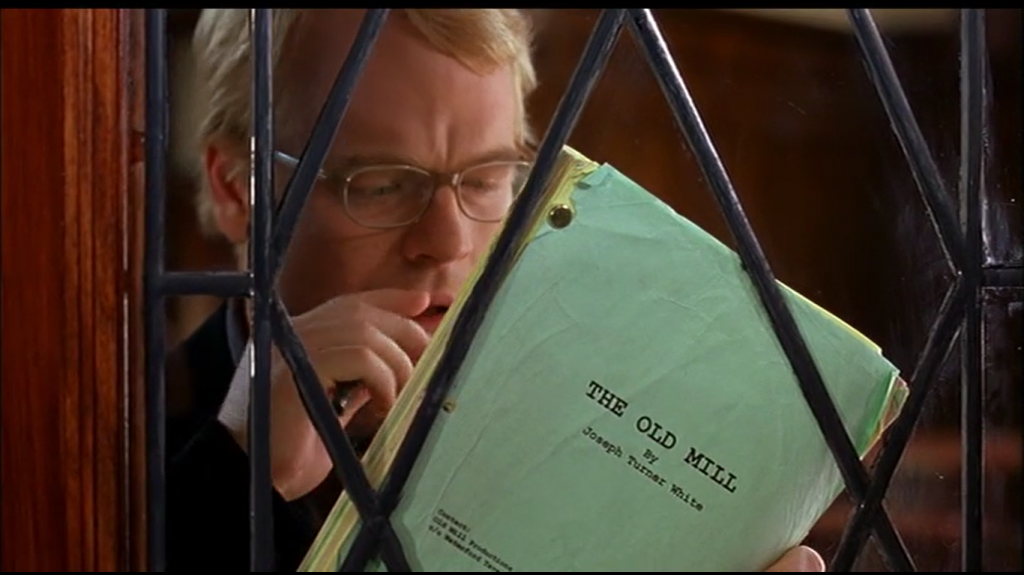

Until, of course, they’ve set up shop only to discover that Waterford’s old mill burned to the ground forty years ago. Joseph (Philip Seymour Hoffman), the film’s screenwriter, is told to rewrite around this setback, the latest in an increasingly absurd laundry list of roadblocks. It sounds easy enough, until the title of the film within a film is revealed.

The immediate culture clash between these uncomplicated townspeople who speak solely in homespun aphorisms and The Old Mill‘s slick-talking industry folk is striking in its simplicity. In its own cartoonish, farcical way, it’s as straightforward an extrapolation of the blue state/red state schism there is. Hollywood is often thought of as Dionysian to a fault, and this preconception is hammered home once it becomes apparent what drove the shoot out of New Hampshire. The film’s lead, Bob Barrenger (Alec Baldwin), has a taste for underage girls, and that perverse gluttony has already gotten them driven out before. His ephebophilia is played more for laughs than anything else, but the sense that the liberal elite want to transform their little burg into a bacchanal is still present, personified in local politician Doug (Clark Gregg) and his quest to exploit the production before it can exploit the town.

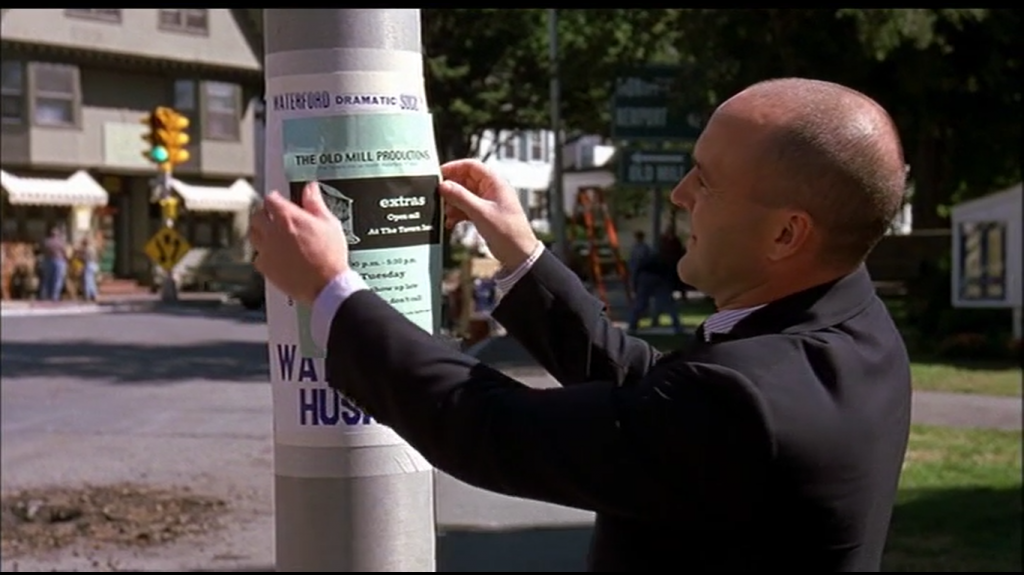

Much of State and Main‘s first act is the fleeting pursuit of equilibrium between these competing ecosystems. From keeping Barrenger away from teenager Carla (Julia Stiles), who works at the town’s diner, to placating his sensitive co-star Claire (Sarah Jessica Parker), who doesn’t want to bare her breasts on screen, Walt has his hands full. Waterford’s Mayor (Charles Durning) and his wife (Patti LuPone) plan an extravagant dinner with the film’s top brass, but a dry erase board accident slates it on the wrong day for the production’s schedule. With that dramatic mishap looming overhead, every infraction between the film’s crew and the town’s inhabitants grows ever more calamitous. Mamet finds plainspoken visual cues to underline this conflict, like notices for a casting call being plastered over flyers advertising a local theater production.

The only two people getting along swimmingly amidst this chaos are Joseph and Ann (Rebecca Pidgeon), a local print shop owner who is a fan of the play Joseph wrote before getting this screenwriting gig. Ann also happens to be Doug’s fiancee. Joseph and Ann begin to develop feelings for one another, which only fuels his disdain for The Old Mill. This coupling, however, is essential to the success of the production. Every new setback requires narrative acrobatics Joseph is too anxious to execute in the rewriting process, but Ann, existing as she does outside of the industry’s torturous game of give and take, offers dramaturgically sound solutions with ease.

The central theme at the heart of The Old Mill, that of purity and second chances, comes to typify State and Main‘s story, as well. There’s an ongoing philosophical debate about integrity, a bedrock of the town’s moral values, versus the convenient dishonesty that drives the movie business forward. The town’s inhabitants largely converse in an easygoing vernacular devoid of deception, but for Walt and his team, every new interaction is a battlefield for supremacy and the only way to win is to lie better than the other guy.

This is present in the film’s endlessly quotable dialogue, even from the film’s opening moments. When Joseph tells Walt he can’t write without his typewriter, Walt casually implies that he can sympathize, because his job is keeping people happy and making them feel like he’s on their side. When Joseph, somewhat offended, calls him on it, Walt defends himself. “It’s not a lie,” he says. “It’s a gift for fiction.” Throughout the film, Walt and, later, producer Marty (David Paymer) trade exclusively in bold-faced lies they transform into gospel through sheer force of will. In their world, declarative statements become their own kind of truth if spoken with enough repetitive conviction.

On the flip side, when Ann catches Joseph with a topless Claire, he struggles to find a lie strong enough to defend himself in this precarious situation and defaults to the truth, despite the inherent strangeness of the predicament. Ann, a fundamentally honest person, takes him at his word.

Joseph: You believe that?

Ann: I do if you do.

Joseph: But that’s absurd.

Ann: So is our electoral process, but we still vote.

The movie business trades in falsehoods, but those fictive machinations are supposed to be in the pursuit of nourishing the audience. Joseph is a storyteller from a medium predicated upon a brand of honesty this depiction of filmmaking just can’t support. His attraction to Ann is presented as Joseph grabbing a hold of the kind of artistic purity he feels himself losing his grip on. This push and pull between what is and isn’t the truth comes to a head when Barrenger is caught in a car accident with Carla and Joseph is the only witness. He has to choose between telling the truth in court and effectively ending his career in movies or lie and lose any respect Ann has for him, or any he has left for himself.

This being a movie, Mamet finds a way for Joseph to have it both ways, through sharp script craft and a convenient confluence of dangling plot threads. It’s a magical kind of conclusion, one that would ring false if the entire picture wasn’t structured in support of such a serendipitous out. That’s what the movie business is all about, though: an unfortunate series of stumbling blocks punctuated by a reassuring conclusion.

Check back in the coming weeks for the next installment of Movies on Movies…

The broad strokes of the plot always remind of the Simpsons’ “Radioactive Man” movie episode where the locals are just as cynical and grasping as the movie folks.