In honor of Netflix’s new Luke Cage series starring Mike Colter, four Deadshirt writers discuss their favorite comics starring Marvel’s hottest superhero. Power Man. Hero for Hire. Avenger. Defender. These are some of the best Luke Cage comics around!

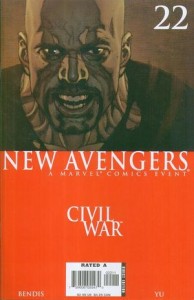

New Avengers #22 (2006)

Written by Brian Michael Bendis

Art by Leinil Francis Yu

Colors by Dave McCaig

My first real exposure to Luke Cage was in the pages of Secret War, before the launch of New Avengers, as I was just getting into comics. Like most first exposures, it’s the version of the character I default to in my head: tough, principled, proud and controlled, a new family man finding himself thrust into the spotlight on a larger stage.

This vision of the character—Brian Michael Bendis’s, which began with the first issue of his and Michael Gaydos’s Alias (introducing Jessica Jones) and continues through his books today—had a lot of great moments in a lot of great stories. But none remain as indelibly lasting in my mind as New Avengers #22, a Civil War tie-in issue with Leinil Francis Yu and Dave McCaig on illustrative duty killing the mood shots and action set-pieces as always. Yu’s shadowy, blockbuster style works perfectly in pencils-only here, with McCaig—one of the best colorists in the business—complementing it perfectly.

The second of five character-focused one-shots, this issue features Luke Cage’s protest against the Superhuman Registration Act. It opens with Tony Stark and Carol Danvers (making this especially whiplash-inducing rereading in the middle of Civil War II) trying to convince Luke and Jessica to register for the sake of their newborn kid. It ends in what’s probably the single best action sequence Bendis has ever written, with Luke fighting an entire squadron of S.H.I.E.L.D. Capekillers with his neighborhood on his side, busting through walls and getting thrown around until Captain America and the other renegade superheroes help him make a getaway. It kicks ass.

But the real steel of the issue is Luke’s moral core; his stubborn refusal to concede a point to Tony and Carol for the sake of pragmatism. By trying to appeal to Luke through his daughter, Tony shot himself in the foot — for, in fact, it’s the very example he has to set for his daughter that forces him to obey his conscience and stand his ground in the face of what he sees as grave injustice.

It’s a superb character piece, a rollicking action comic, a gripping moral drama and, miraculously, an event tie-in all at once. It’s not the best Luke Cage comic of all time; I haven’t read enough Cage books to make a statement like that. I do know that it’s the one that defines him the most to me. I’m excited to see Coker and Colter’s take on him, which from trailers and promotional material (not to mention Colter’s performance in Jessica Jones) seems to be greatly inspired by that take.

— David Uzumeri

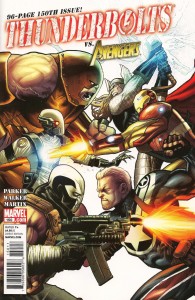

Thunderbolts #150 (2010)

Written by Jeff Parker

Art by Kev Walker

Brian Michael Bendis was largely responsible for Luke Cage becoming a top-tier Marvel character in his tenure on multiple Avengers titles, but Cage’s first major post-Bendis book is criminally underrated. Jeff Parker (along with artists Kev Walker and Declan Shalvey) delivered the “Heroic Age” Thunderbolts book, which found Luke Cage in charge of a new super-villain rehabilitation program meant to put villains like Ghost, Juggernaut, Crossbones, and Moonstone to good use on missions around the globe.

The book’s similarities to DC’s Suicide Squad are too pronounced to be a coincidence—a bunch of career super-criminals sent into Marvel Universe grease fires by a strong-willed African-American leader constantly at odds with their own team—but with a major difference: Luke Cage is an ex-con and the Thunderbolts are more than expendable collateral assets. Cage, who was tortured by Norman Osborn’s sadistic version of the Thunderbolts towards the end of “Dark Reign,” agrees to take charge of the team in order to provide some bad guys a chance to make good. Positing Luke, a man who knows all too well what it’s like to be on the inside, as a sort of parole officer for bad guys, was a great attempt to show just how far Luke Cage has come since his inception in the 1970s. Parker explores the idea of redemption throughout his run: If Luke Cage can go from former inmate to Avenger, can other cons? Can someone like The Juggernaut be more than just an unstoppable engine of destruction? Can a vile murderer like Crossbones be redeemed? Is the program even a good idea?

Thunderbolts #150, a double-sized issue with some of Shalvey’s best work on the title, brings all of these ideas to an interesting semi-conclusion. The issue finds Luke and a trio of guest-starring Avengers teleported to another dimension after Ghost, Juggernaut and Crossbones attempt a jailbreak that goes haywire. While Crossbones inevitably tries to kill Captain America and is formally kicked off the team, Juggernaut and Ghost reach a kind of peace with their superhero counterparts (Cage and Iron Man, respectively). For one day, at least, Luke Cage’s mission worked. When he’s asked what he sees in the other dimensional realm’s magic waters, which show the viewer their “true” self, Cage only sees his reflection staring back at him. “Maybe you all see something else, Steve…but I just see me.”

— Max Robinson

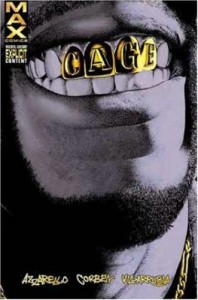

Cage #1-4 (2002)

Written by Brian Azzarello

Art by Richard Corben

Colors by Jose Villarrubia

Letters by Wes Abbott

Luke Cage has been many things throughout his storied Marvel history. A tiara-wearing superhero, The Punisher’s personal liaison to blackness when Frank Castle was briefly a person of color, even a team leader and father. But right before Brian Michael Bendis went full bore into the years-long Cage arc that began in earnest in Alias #1, crime fiction enthusiast Brian Azzarello had a different vision for the former Power Man. Azzarello saw Cage as Ving Rhames.

And so did artist Richard Corben, from the look of the interior art of 2002’s Cage miniseries, courtesy of Marvel’s “adult” line MAX. Just look at him in his first full panel. In his bubble vest, Timberland boots and winter cap, Cage has every thickly built, hard nosed characteristic Rhames possessed in John Singleton’s then-recent film Baby Boy. He looked more like someone’s St. Ives-swilling uncle than ever before. The duo’s interpretation of the iconic hero had so little to do with superheroics, choosing instead to plop Cage into a gritty pulp version of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, westernized into Fistful of Dollars before being reskinned to the ghetto for this bullet-riddled exploitation comic. (Both owing heavily to Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest.)

The plot is rather threadbare. Cage, having been hired to investigate the murder of a young girl, gets caught in a tangled web of crime, graft and some depressingly relevant commentary on gentrification. Along the way, his origin is briefly revisited for the new readers this glaring stylistic departure hoped to bring in. It’s a brisk, thrilling read. One better read as an individual, trade length statement on the character than as any kind of sustainable, sequential franchise reset. Cage, if nothing else, is the blueprint for the Joker OGN Azzarello would go onto create with Lee Bermejo. The hard edged, painterly visuals and mature subject matter, gleefully divorced from the four color constraints of cape comics? That’s all from here.

Corben’s art makes an instant impression, bursting off the page with blaxploitation swagger and a pugilist’s precision with lines. The whole book feels like it was itched in rubble with a pickax and colored in by Villarrubia with a backpack full of spray paint cans. On a visual level, it’s filled to the brim with deft storytelling techniques (the first issue does some amazing things with the use of mirrors), but the book is hindered by its slavish attempts at street talk credibility.

Anyone who’s read 100 Bullets knows Azzarello’s penchant for dialect-driven banter can careen wildly between pitch perfect found dialogue to borderline offensive caricature within the span of a scant few world bubbles. If early Luke Cage comics were typified by out-of-touch white writers cluelessly aping the cartoonish hood poetry of Chester Himes, Cage feels like a script from The Wire, removed from David Simon’s Rick Rubinesque skill for reduction. Azzarello overstuffs every interaction with distracting phoenetics and purposely obtuse vernacular in a way that reads more like a white dude trying prove he’s down from the safety of a keyboard than the pursuit of narrative authenticity.

Those gripes aside, Cage is an entertaining read. It’s the kind of left field reimagining that serves more to expand the strictures of how a legacy character can be presented than as a true building block for a successful ongoing. There’s something in this book’s noirish dynamism that has endured despite its authorial voice aging so poorly. Comics being a visual medium, Corben’s art outshines Azzarello’s writing, and the influence of his reinterpretation is still felt with the character’s look in today’s books, as well as the new Netflix series.

— Dominic Griffin

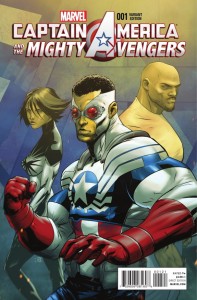

Captain America and the Mighty Avengers #1-6 (2014)

Written by Al Ewing

Art by Luke Ross and Iban Coello

Colors by Rachelle Rosenberg

Lettered by Cory Petit

Al Ewing consistently makes lemonade out of the lemons he’s handed by Marvel events. AXIS was not a strong event, by any means, but the relaunch of Mighty Avengers provided a great springboard for an interesting look at what makes Luke Cage work.

In AXIS, a bunch of Marvel characters are hit with an “inversion spell” that brings out their worst attributes. Cage’s new deal under the spell is fancy clothes, franchising deals, and a moral void he fills with greed and pride. Ewing’s portrayal of an evil Cage really gets to the core of the character: his integrity. Luke Cage is a quintessentially grounded hero, and even in his rise to A-list status under Bendis, the core value of street level crimefighting and protecting his community remained. Ewing pushed this concept to the forefront in Mighty Avengers, with Cage heading up a community-minded successor team to Heroes for Hire.

With this foundation in place, Ewing wrote a Cage who gives in to his worst impulses, one whose greed alienates him from his team, his friends, and his wife. It’s weird to characterize a “best” Luke Cage story as one where he’s behaving totally out of character, but that juxtaposition just drives home the understanding Ewing has of the character. When he’s inevitably turned back to normal, he engages in a long con to permanently defeat one of his archenemies, making the best of a bad situation. Ewing’s Luke Cage is like the best takes on Superman: he’s flawed and imperfect, but pushes himself to rise to the occasion.

— Joe Stando

The first season of Marvel’s Luke Cage hits Netflix this weekend.