Welcome to Angry Turtle!, a series featuring Deadshirt.net’s own Patrick Stinson and guest writer Andrew Tucker. We are going to be looking at the Gamera series, the films made by a rival studio to compete directly with the famous Godzilla series. The name comes from this charming video.

Patrick: Welcome back to Angry Turtle! Sorry for the delay. We’re teachers, what can you do?

Andrew: Gotta teach them kids.

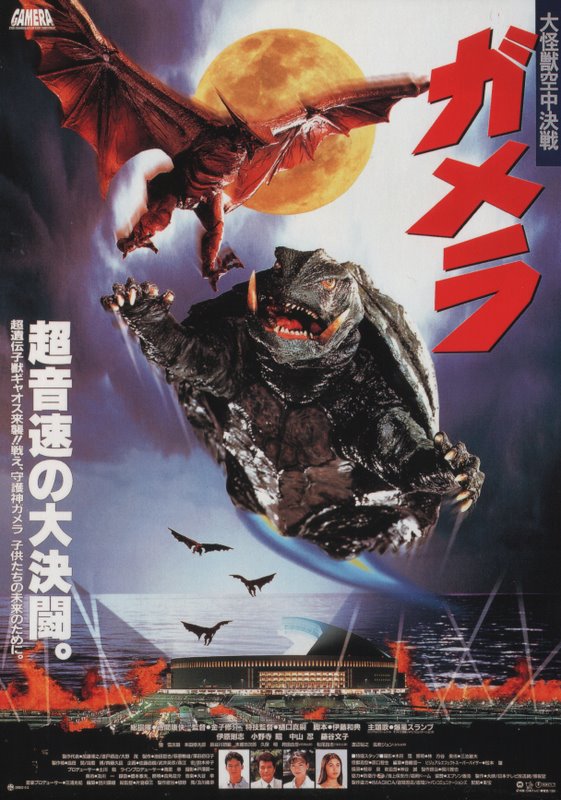

Patrick: What we have here is the first of the Gamera Trilogy, otherwise known as the Heisei series after the imperial reign that was current then (and is now). Gamera: Guardian of the Universe was released at the beginning of 1995 by Daiei Studios after yet another restructuring. At this time, Godzilla’s own Heisei series was doing big business in Japan, so resurrecting Godzilla’s rival was a smart move. But moviegoers had changed. The kiddy approach was not going to cut it. Gamera had to offer something new.

Andrew: This film coincided with the penultimate Heisei Godzilla movie, Godzilla vs. Spacegodzilla, which ironically abandoned the more mature approach of the previous Heisei films for a lighter tone and, unfortunately, did little to impress. In fact, Godzilla’s series was meant to end before Spacegodzilla in favor of an American series, but the American studios stalled and Toho had to pump another two movies out before TriStar eventually got the ball rolling. Gamera, on the other hand, came roaring into theaters and ushered in a truly great return for Godzilla’s box office rival.

Patrick: What they did was hire director Shusuke Kaneko and special effects artist Shinji Higuchi, the former of whom later directed the acclaimed Godzilla Mothra King Ghidorah in 2001 and the latter recently co-directed Shin Godzilla. These two gentlemen represented the second generation of kaiju filmmakers in a way that the Heisei Godzilla producers did not. They presented Gamera just as his original incarnation—a hulking Atlantean pyrokinetic turtle—but in a more grounded world with palpable stakes. In this film the Gyaos isn’t harassing one city, it’s about to become a global outbreak of indestructible supersonic people-eaters.

Andrew: What both Heisei series did which really set them apart from the earlier Showa series was ground these kaiju in science fiction-fantasy. These monsters become metaphors for humanity’s problems with the environment and technology in a way few earlier films explored, save for maybe the original Gojira (1954) and the Mothra movies. Gamera is a guardian, not a superhero. He is protecting Earth, not childhood fantasies. An ancient civilization creates the Gyaos, which run amok, and so they create Gamera to counter their precious mistake. Gamera fights for the protection of Earth in a very similar way Gareth Edwards’ 2014 Godzilla does.

Patrick: I’m glad you mention 2014’s Godzilla, because it’s very striking how much that film borrows from this one. Both follow the same basic structure of “team of scientists discover good monster and bad monster but military can’t tell them apart.” I’m sure it’s unwitting, there are just only so many “origin stories” for kaiju.

Andrew: I’ve never thought about that. Both feature the titular monster coming out of the sea as an ancient behemoth to fight paleolithic demon birds with the ability to use energy as a weapon. What makes this Gamera movie stand out from other kaiju movies, however, is the mysterious connection between Gamera and Asagi, a seemingly innocent girl who stumbles into the relics of Gamera’s past and develops a corporal bond with him. Her connection is not explained in this movie, but it adds a tragic undertone to an otherwise fun, adventurous flick. Oh, and the Gyaos eat people again. So that’s dark, too.

Patrick: The story of the movie is simplicity itself—two shipping employees investigate a mysterious atoll, which turns out to be a hibernating Gamera. It wakes up when an ornithologist, Nagamine, discovers three smaller monsters, the Gyaos. The government, not unsensibly, comes up with a plan to trap these “endangered organisms.” When Gamera starts trying to annihilate them and crashes through Fukuoka to do it, they again, not unsensibly, use military force to try to stop him. What Gamera knows and they don’t is that the Gyaos keep growing and are about to reproduce. They have to eat people, and Gamera was built by the ancients to stop them. The diplomatic link between Gamera and humanity is ultimately forged by Asagi, played by (and I am not making this up) Steven Seagal’s daughter.

Andrew: As Gamera is injured, so is Asagi. In a throwback to the original, Gyaos cuts through Gamera’s hand. When this happens, Asagi shares the wound. This is beautiful symbolism that was previously absent from the more heavy-handed messaging of the latter Heisei Godzilla films. Asagi acts as our Miki Saegusa character, the psychic that appears in all but one of the Heisei Godzilla movies. Asagi is our through-line as we watch Gamera develop over the trilogy into a truly tragic hero.

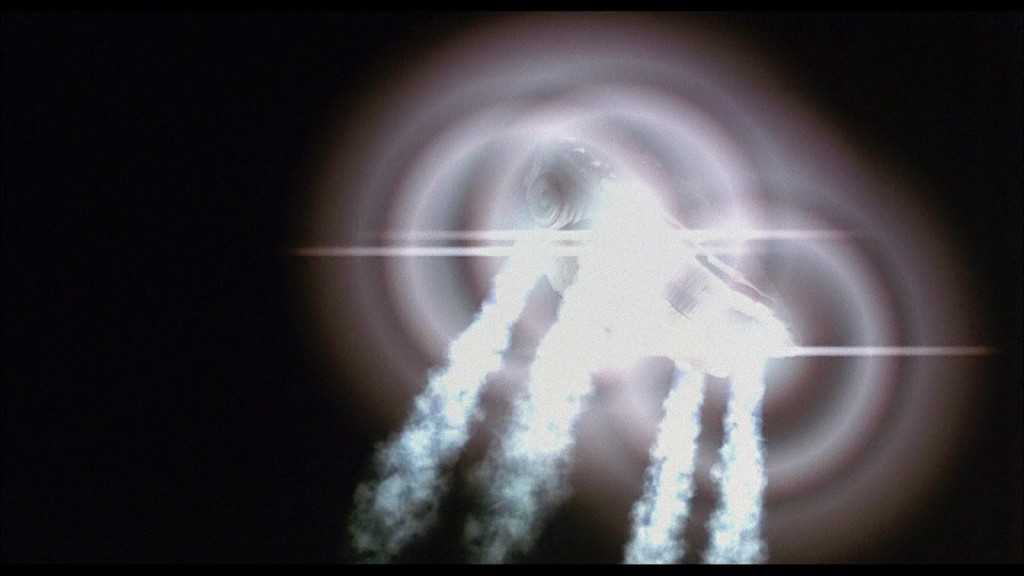

Patrick: The most striking element of this movie is the visual innovation involved. Jurassic Park was only two years down, and yet this movie is using computer-generated effects to supplement the puppets and suits for the first time in the Japanese effects industry. This is despite a budget that was less than one million dollars. It cleans the clock of the contemporary Godzilla films and just about manages to hold up today. Most notably, Gamera’s flight is a completely animated effect rather than the old “resin shell plus gunpowder on wire,” and his flamethrower has been replaced with “plasma balls” that pack an amazing wallop.

Andrew: They also decided not scale up their monsters as Toho had, and instead hired little people to play the monsters. This allows for more detail in their city sets and gives more room for interesting flares in the kaiju suits. Most notably, Gamera is incredibly expressive. The Heisei series did a lot to make Godzilla a more emotional character—it happens to be my favorite incarnation. With Gamera, however, there’s an energy brought about with the flinging of his head and neck that makes every shot with him exciting. They also make Gyaos look demonic while still maintaining the same silhouette as the original. I will say, though, that the human characters aside from Asagi can become quite boring and are often relegated to exposition and reaction unlike the very diverse casts of the Heisei Godzilla movies. It’s the same critique that is often made of Edwards’ cast in Godzilla (2014).

Patrick: It’s hard to tell how much was foreseen in advance, but in retrospect much of the strength of this movie is how concepts merely hinted at here—like the energy Gamera calls on, or the nature of his connection to Asagi—are fleshed out into elements of an epic storyline in the next two movies.

Andrew: The triumph of this movie lies in its brilliant reintroduction of a washed-up kaiju with grounded and exciting action and threads of continuity that develop not only the story but Gamera as a character that actually evolves over the course of his new trilogy.

Patrick: Next up we see what’s next for Gamera and Asagi. Their foes are legion…

Andrew: They mostly come at night. Mostly.